Steam Turbine

Since the steam turbine is a rotary heat engine, it is particularly suited to drive an electrical generator. Note that about 90% of all electricity generation in the world is by use of steam turbines. Steam turbine was invented in 1884 by Sir Charles Parsons, whose first model was connected to a dynamo that generated 7.5 kW (10 hp) of electricity. The steam turbine is a common feature of all modern and also future thermal power plants. Also, the power production of fusion power plants is based on the use of conventional steam turbines.

See also: Properties of Steam

How does a steam turbine work?

The thermal energy contained in the steam is converted to mechanical energy by expansion through the turbine. The expansion takes place through a series of fixed blades (nozzles) that orient the steam flow into high-speed jets. These jets contain significant kinetic energy, which is converted into shaft rotation by the bucket-like shaped rotor blades as the steam jet changes direction (see: Law of conversation of momentum). In moving over the curved surface of the blade, the steam jet exerts pressure on the blade owing to its centrifugal force. Each row of fixed nozzles and moving blades is called a stage. The blades rotate on the turbine rotor, and the fixed blades are concentrically arranged within the circular turbine casing.

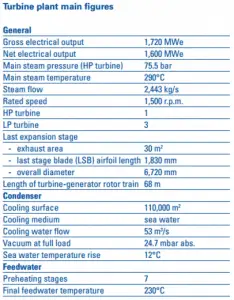

In all turbines, the rotating blade velocity is proportional to the steam velocity passing over the blade. If the steam is expanded only in a single stage from the boiler pressure to the exhaust pressure, its velocity must be extremely high. But the typical main turbine in nuclear power plants, in which steam expands from pressures about 6 MPa to pressures about 0.008 MPa, operates at speeds about 3,000 RPM for 50 Hz systems for 2-pole generator (or 1500RPM for 4-pole generator), and 1800 RPM for 60 Hz systems for 4-pole generator (or 3600 RPM for 2-pole generator). A single-blade ring would require very large blades and approximately 30 000 RPM, too high for practical purposes.

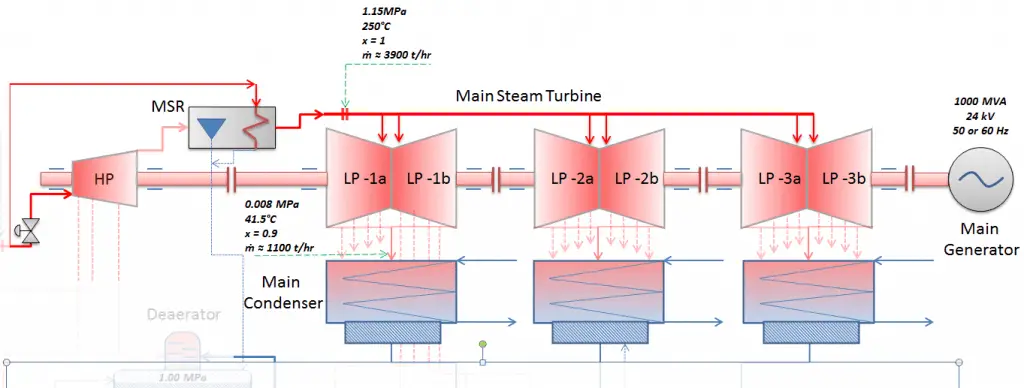

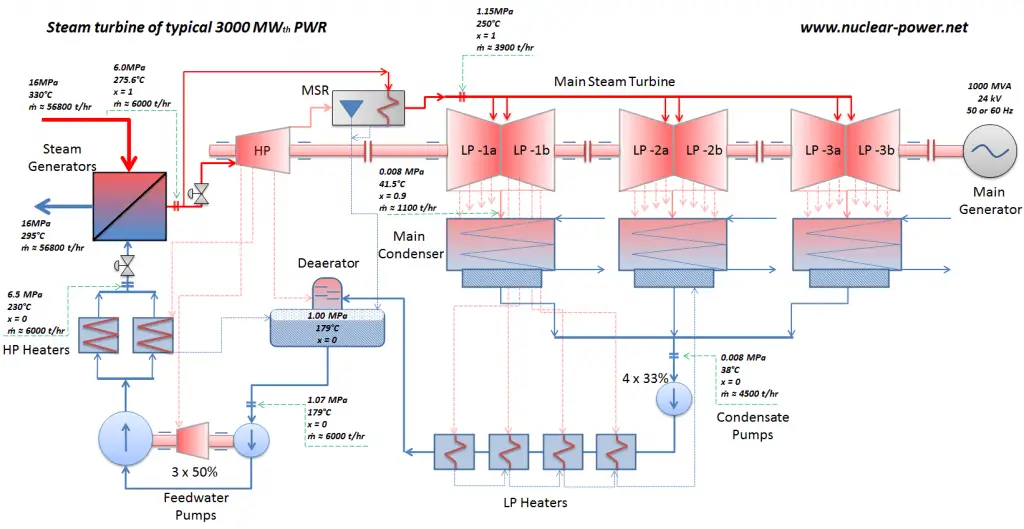

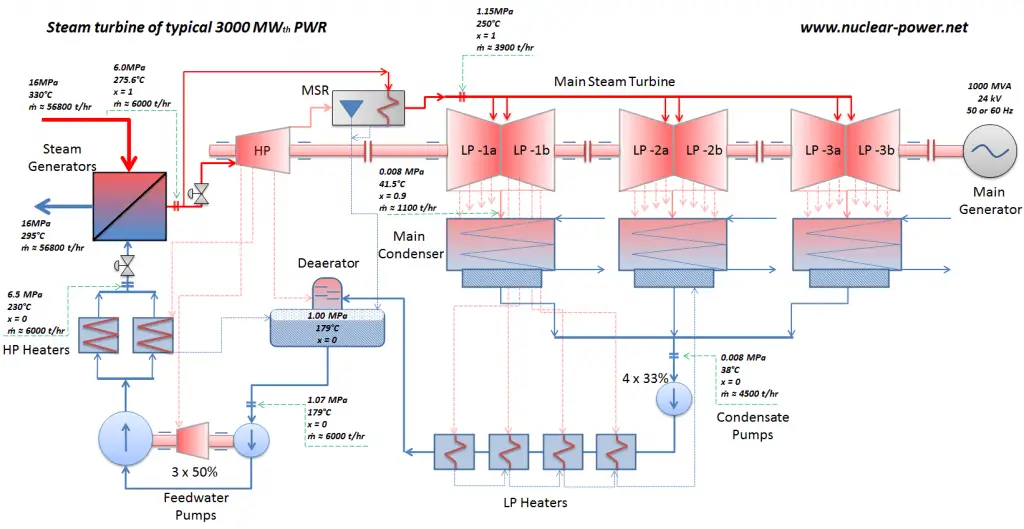

Therefore most nuclear power plants operate a single-shaft turbine-generator that consists of one multi-stage HP turbine and three parallel multi-stage LP turbines, the main generator and an exciter. HP Turbine is usually a double-flow reaction turbine with about 10 stages with shrouded blades and produces about 30-40% of the gross power output of the power plant unit. LP turbines are usually double-flow reaction turbines with about 5-8 stages (with shrouded blades and free-standing blades of the last 3 stages). LP turbines produce approximately 60-70% of the gross power output of the power plant unit. Each turbine rotor is mounted on two bearings, i.e., there are double bearings between each turbine module.

See also: HP Turbine

See also: LP Turbine

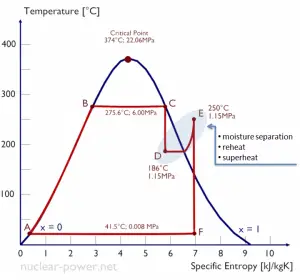

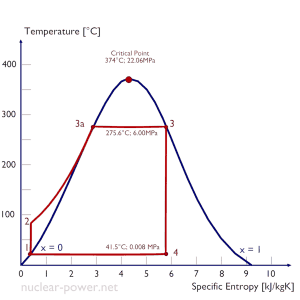

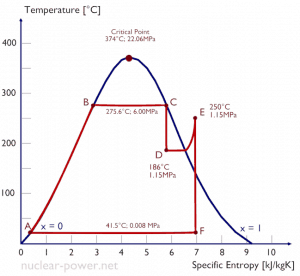

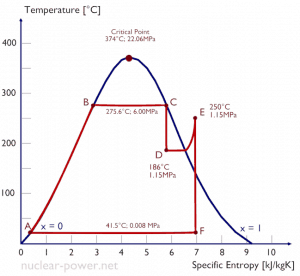

In these turbines, the high-pressure stage receives steam (this steam is nearly saturated steam – x = 0.995 – point C at the figure; 6 MPa; 275.6°C) from a steam generator and exhausts it to moisture separator-reheater (point D). The steam must be reheated to avoid damages caused to the steam turbine blades by low-quality steam. The reheater heats the steam (point D), and then the steam is directed to the low-pressure stage of the steam turbine, where it expands (point E to F). The exhausted steam then condenses in the condenser. It is at a pressure well below atmospheric (absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa) and is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%.

Types of Steam Turbines

Steam turbines may be classified into different categories depending on their construction, working pressures, size, and other parameters. But there are two basic types of steam turbines:

- impulse turbines

- reaction turbines.

The main distinction is how the steam is expanded as it passes through the turbine.

Impulse Turbine and Reaction Turbine

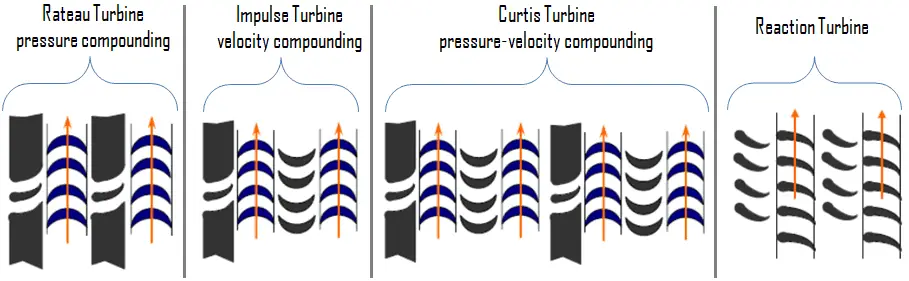

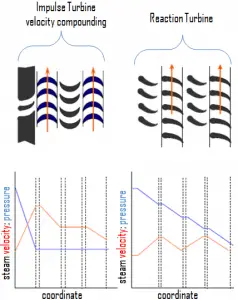

Steam turbine types based on blade geometry and energy conversion process are impulse turbine and reaction turbine.

Impulse Turbine

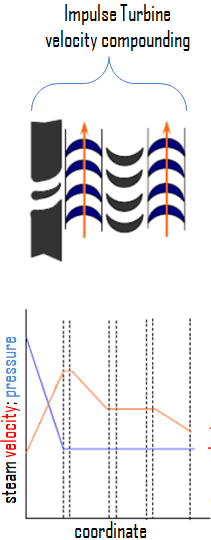

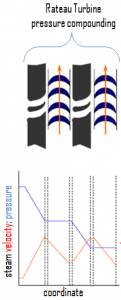

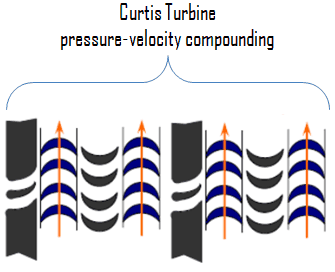

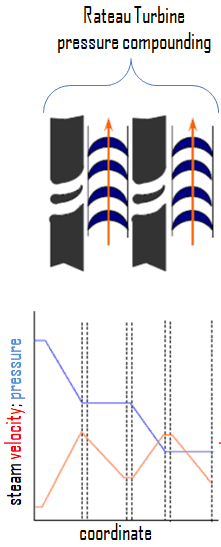

The impulse turbine is composed of moving blades alternating with fixed nozzles. The steam is expanded in fixed nozzles in the impulse turbine and remains at constant pressure when passing over the blades. Curtis turbine, Rateau turbine, or Brown-Curtis turbine are impulse type turbines. The original steam turbine, the De Laval, was an impulse turbine having a single-blade wheel.

The impulse turbine is composed of moving blades alternating with fixed nozzles. The steam is expanded in fixed nozzles in the impulse turbine and remains at constant pressure when passing over the blades. Curtis turbine, Rateau turbine, or Brown-Curtis turbine are impulse type turbines. The original steam turbine, the De Laval, was an impulse turbine having a single-blade wheel.

The entire pressure drop of steam takes place in stationary nozzles only. Though the theoretical impulse blades have zero pressure drop in the moving blades, practically, for the flow to take place across the moving blades, there must be a small pressure drop across the moving blades also.

The steam expands through the nozzle in impulse turbines, where most of the pressure potential energy is converted to kinetic energy. The high-velocity steam from fixed nozzles impacts the blades changes its direction, which in turn applies a force. The resulting impulse drives the blades forward, causing the rotor to turn. The main feature of these turbines is that the pressure drop per single stage can be quite large, allowing for large blades and a smaller number of stages. Except for low-power applications, turbine blades are arranged in multiple stages in series, called compounding, which greatly improves efficiency at low speeds.

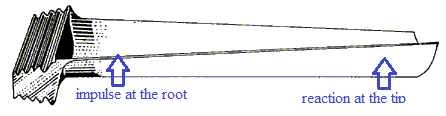

Modern steam turbines frequently employ both reaction and impulse in the same unit, varying the degree of reaction and impulse from the blade root to its periphery. The rotor blades are usually designed like an impulse blade at the rot and a reaction blade at the tip.

Since the Curtis stages reduce the pressure and temperature of the fluid significantly to a moderate level with a high proportion of work per stage, a usual arrangement is to provide one or more Curtis stages on the high-pressure side, followed by Rateau or reaction staging. In general, when friction is taken into account reaction stages, the reaction stage is found to be the most efficient, followed by Rateau and Curtis in that order. Frictional losses are significant for Curtis stages since these are proportional to steam velocity squared. Frictional losses are less significant in the reaction stage because the steam expands continuously, so flow velocities are lower.

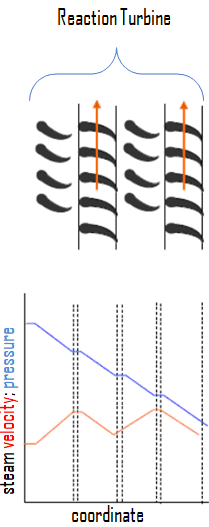

Reaction Turbine – Parsons Turbine

The reaction turbine is composed of moving blades (nozzles) alternating with fixed nozzles. In the reaction turbine, the steam is expanded in fixed nozzles and also in the moving nozzles. In other words, the steam is continually expanding as it flows over the blades. There is pressure and velocity loss in the moving blades. The moving blades have a converging steam nozzle. Hence when the steam passes over the fixed blades, it expands with a decrease in steam pressure and increases in kinetic energy.

The reaction turbine is composed of moving blades (nozzles) alternating with fixed nozzles. In the reaction turbine, the steam is expanded in fixed nozzles and also in the moving nozzles. In other words, the steam is continually expanding as it flows over the blades. There is pressure and velocity loss in the moving blades. The moving blades have a converging steam nozzle. Hence when the steam passes over the fixed blades, it expands with a decrease in steam pressure and increases in kinetic energy.

The steam expands through the fixed nozzle in reaction turbines, where the pressure potential energy is converted to kinetic energy. The high-velocity steam from fixed nozzles impacts the blades (nozzles), changes their direction, and undergoes further expansion. The change in its direction and the steam acceleration applies a force. The resulting impulse drives the blades forward, causing the rotor to turn. There is no net change in steam velocity across the stage but with a decrease in pressure and temperature, reflecting the work performed in the driving of the rotor. In this type of turbine, the pressure drops occur in many stages because the pressure drop in a single stage is limited.

The main feature of this type of turbine is that the pressure drop per stage is lower than the impulse turbine, so the blades become smaller, and the number of stages increases. On the other hand, reaction turbines are usually more efficient, i.e., they have higher “isentropic turbine efficiency”. The reaction turbine was invented by Sir Charles Parsons and is known as the Parsons turbine.

In the case of steam turbines, such as would be used for electricity generation, a reaction turbine would require approximately double the number of blade rows as an impulse turbine for the same degree of thermal energy conversion. While this makes the reaction turbine much longer and heavier, the overall efficiency of a reaction turbine is slightly higher than the equivalent impulse turbine for the same thermal energy conversion.

Modern steam turbines frequently employ both reaction and impulse in the same unit, varying the degree of reaction and impulse from the blade root to its periphery. The rotor blades are usually designed like an impulse blade at the rot and a reaction blade at the tip.

Classification of Turbines – steam supply and exhaust conditions

Steam turbines may be classified into different categories depending on their purpose and working pressures. The industrial usage of a turbine influences the initial and final conditions of steam. A pressure difference must exist between the steam supply and the exhaust for any steam turbine to operate.

This classification includes:

- Condensing Steam Turbine,

- Back-pressure Steam Turbine,

- Reheat Steam Turbine,

- Turbine with Steam Extraction

Turbine Blades

The most important turbine elements are the turbine blades. They are the principal elements that convert the pressure energy of working fluid into kinetic energy. Turbine blades are of two basic types:

- moving blades

- fixed blades

The steam expands through the fixed blade (nozzle) in steam turbines, where the pressure potential energy is converted to kinetic energy. The high-velocity steam from fixed nozzles impacts the moving blades changes its direction and also expands (in the case of reaction-type blades). The change in its direction and the steam acceleration (in the case of reaction-type blades) applies a force. The resulting impulse drives the blades forward, causing the rotor to turn. Steam turbine types based on blade geometry and energy conversion process are:

- impulse turbine

- reaction turbine

Modern steam turbines frequently employ both reaction and impulse in the same unit, typically varying the degree of reaction and impulse from the blade root to its periphery. The rotor blades are usually designed like an impulse blade at the rot and a reaction blade at the tip.

The efficiency and reliability of a turbine depend on the proper design of the blades. It is, therefore, necessary for all engineers involved in turbines engineering to have an overview of the importance and the basic design aspects of the steam turbine blades. The engineering of turbine blades is a multi-disciplinary task. It involves thermodynamics, aerodynamics, mechanical and material engineering.

The efficiency and reliability of a turbine depend on the proper design of the blades. It is, therefore, necessary for all engineers involved in turbines engineering to have an overview of the importance and the basic design aspects of the steam turbine blades. The engineering of turbine blades is a multi-disciplinary task. It involves thermodynamics, aerodynamics, mechanical and material engineering.

For gas turbines, the turbine blades are often the limiting component. The highest temperature in the cycle occurs at the end of the combustion process, and it is limited by the maximum temperature that the turbine blades can withstand. As usual, metallurgical considerations (about 1700 K) place upper limits on thermal efficiency. Therefore turbine blades often use exotic materials like superalloys and many different methods of cooling, such as internal air channels, boundary layer cooling, and thermal barrier coatings. The development of superalloys in the 1940s and new processing methods such as vacuum induction melting in the 1950s greatly increased the temperature capability of turbine blades. Modern turbine blades often use nickel-based superalloys that incorporate chromium, cobalt, and rhenium.

Steam turbine blades are not exposed to such high temperatures, but they must withstand an operation with two-phase fluid. High content of water droplets can cause rapid impingement and erosion of the blades, which occurs when condensed water is blasted onto the blades. For example, condensate drains are installed in the steam piping leading to the turbine to prevent this. Another challenge for engineers is the design of blades of the last stage of the LP turbine. These blades must be (due to high specific volume of steam) very long, which induces enormous centrifugal forces during operation. Therefore, turbine blades are subjected to stress from centrifugal force (turbine stages can rotate at tens of thousands of revolutions per minute (RPM), but usually at 1800 RPM) and fluid forces that can cause a fracture, yielding, or creep failures.

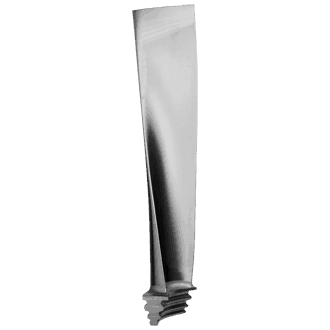

Turbine Blades – Root, Profile, Shroud

Turbine blades are usually divided into three parts:

- Root. The root is a constructional feature of turbine blades, which fixes the blade into the turbine rotor.

- Profile. The profile converts the kinetic energy of steam into the mechanical energy of the blade.

- Shroud. The shroud reduces the blade’s vibration, which the flowing high-pressure steam can induce through the blades.

Losses in Steam Turbines

The steam turbine is not a perfect heat engine. Energy losses tend to decrease the efficiency and work output of a turbine. This inefficiency can be attributed to the following causes.

- Residual Velocity Loss. The velocity of the steam that leaves the turbine must have a certain absolute value (vex). The energy loss due to the absolute exit velocity of steam is proportional to (vex2/2). This type of loss can be reduced by using a multi-stage turbine.

- Presence of Friction. In real thermodynamic systems or real heat engines, a part of the overall cycle inefficiency is due to the frictional losses by the individual components (e.g.,, nozzles or turbine blades)

- Steam Leakage. The turbine rotor and the casing cannot be perfectly insulated. Some amount of steam leaks from the chamber without doing useful work.

- Loss Due to Mechanical Friction in Bearings. Each turbine rotor is mounted on two bearings, i.e., there are double bearings between each turbine module.

- Pressure Losses in Regulating Valves and Steam Lines. The main steam line isolation valves (MSIVs) are the throttle-stop valves and control valves between steam generators and the main turbine. Like pipe friction, the minor losses are roughly proportional to the square of the flow rate. The flow rate in the main steam lines is usually very high. Although throttling is an isenthalpic process, the enthalpy drop available for work in the turbine is reduced because this causes an increase in the vapor quality of outlet steam.

- Losses Due to Low Quality of Steam. The exhausted steam is at a pressure well below atmospheric, and the steam is in a partially condensed state, typically of a quality near 90%. Higher content of water droplets can cause rapid impingement and erosion of the blades, which occurs when condensed water is blasted onto the blades.

- Radiation Loss. The steam turbine may operate at a steady state with inlet conditions of 6 MPa, t = 275.6°. Since it is a large and heavy machine, it must be thermally insulated to avoid any heat loss to the surroundings.

Governing of Steam Turbine

Governing of steam turbine is the procedure of controlling the flow rate of steam to a steam turbine to maintain the speed of the turbine fairly constant irrespective of load on the turbine. The typical main turbine in nuclear power plants, in which steam expands from pressures about 6 MPa to pressures about 0.008 MPa, operates at speeds about:

- 3000 RPM for 50 Hz systems for 2-pole generator (or 1500RPM for 4-pole generator),

- 1800 RPM for 60 Hz systems for 4-pole generator (or 3600 RPM for 2-pole generator).

The variation in load (power output) during the operation of a steam turbine can have a significant impact on its performance and its efficiency. Traditionally, nuclear power plants (NPPs) have been considered baseload sources of electricity as they rely on technology with high fixed costs and low variable costs. However, this simple state of affairs no longer applies in all countries. The share of nuclear power in the national electricity mix of some countries has become so large that the utilities have had to implement or improve the maneuverability capabilities of their power plants to adapt the electricity supply to daily, seasonal, or other variations in power demand. For example, this is the case in France, where more than 75% of electricity is generated by NPPs, and where some nuclear reactors operate in load-following mode.

The primary objective in the steam turbine operation is to maintain a constant speed of rotation irrespective of the varying load. This can be achieved using governing in a steam turbine. The principal methods of governing which are used in steam turbines are:

-

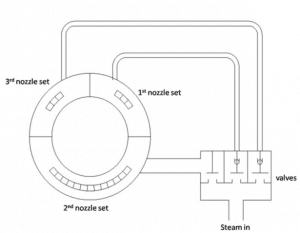

Nozzle Governing. Source: wikipedia.org License: CC BY-SA 3.0 Throttle governing. The main parts of a simple throttle governing system are the throttle-stop valves and especially control valves between steam generators and the main turbine. The primary aim of control valves is to reduce the steam flow rate. Incidental to reducing the mass rate of flow, the steam experiences an increasing pressure drop across the control valve, which is an isenthalpic process. Although throttling is an isenthalpic process, the enthalpy drop available for work in the turbine is reduced because this causes an increase in the vapor quality of outlet steam.

- Nozzle governing. In the nozzle control governing, the steam supply from the main valve is divided into two, three, or more lines. The flow rate of steam is regulated by the opening and shutting of sets of nozzles rather than regulating its pressure.

- Bypass governing. This is generally used for the overload valve, which passes the steam directly into the latter stages of the steam turbine. During such operation, bypass valves are opened, and live steam is introduced into the later stages of the turbine. This generates more energy to satisfy the increased load.

- Combination of 2 and 3.

Turbine Trip

Every steam turbine is also provided with emergency governors who come into action under specific conditions. In general, an unplanned or emergency shutdown of a turbine is known as a “turbine trip”. The turbine trip signal initiates fast closure of all steam inlet valves (e.g.,, turbine stop valves – TSVs) to block steam flow through the turbine.

The turbine trip event is a standard postulated transient, which must be analyzed in the Safety Analysis Report (SAR) for nuclear power plants.

In a turbine trip event, a malfunction of a turbine or reactor system causes the turbine to trip off the line by abruptly stopping the steam flow to the turbine. The common causes for a turbine trip are, for example:

- the speed of the turbine shaft increases beyond specific value (e.g.,, 110%) – turbine overspeed

- balancing of the turbine is disturbed or due to high vibrations

- failure of the lubrication system

- low vacuum in the condenser

- manual emergency turbine trip

Following a turbine trip, the reactor is usually tripped directly from a signal derived from the system. On the other hand, the reactor protection system initiates a turbine trip signal whenever a reactor trip occurs. Since there remains energy in the nuclear steam supply system (NSSS), the automatic turbine bypass system will accommodate the excess steam generation.

Materials for Steam Turbines

The range of alloys used in steam turbines is relatively small, partly because of the need to ensure a good match of thermal properties, such as expansion and conductivity, and partly because of the need for high-temperature strength at an acceptable cost.

- Material for turbine rotors. The rotors of steam turbines are usually made of low-alloy steel. The role of the alloying elements is to increase hardenability to optimize mechanical properties and toughness after heat treatment. The rotors must handle the highest steam conditions; therefore, the alloy most commonly used is CrMoV steel.

- Material for the casing. The casings of steam turbines typically are large structures with complex shapes that must provide pressure containment for the steam turbine. Because of the size of these components, their cost has a strong impact on the overall cost of the turbine. The materials used for inner and outer casings are usually low-alloy CrMo steels (e.g.,, the 1-2CrMo steel). For higher temperatures, cast 9CrMoVNb alloys are considered to be adequate in terms of strength.

- Material of turbine blading. For gas turbines, the turbine blades are often the limiting component. The highest temperature in the cycle occurs at the end of the combustion process, and it is limited by the maximum temperature that the turbine blades can withstand. As usual, metallurgical considerations (about 1700 K) place upper limits on thermal efficiency. Therefore turbine blades often use exotic materials like superalloys and many different methods of cooling, such as internal air channels, boundary layer cooling, and thermal barrier coatings. The development of superalloys in the 1940s and new processing methods such as vacuum induction melting in the 1950s greatly increased the temperature capability of turbine blades. Modern turbine blades often use nickel-based superalloys that incorporate chromium, cobalt, and rhenium.

- Steam turbine blades are not exposed to such high temperatures, but they must withstand an operation with two-phase fluid. The high content of water droplets can cause rapid impingement and erosion of the blades, which occurs when condensed water is blasted onto the blades. To prevent this, for example, condensate drains are installed in the steam piping leading to the turbine. Another challenge for engineers is the design of blades of the last stage of the LP turbine. These blades must be (due to high specific volume of steam) very long, which induces enormous centrifugal forces during operation. Therefore, turbine blades are subjected to stress from centrifugal force (turbine stages can rotate at tens of thousands of revolutions per minute (RPM), but usually at 1800 RPM) and fluid forces that can cause a fracture, yielding, or creep failures.

See also: Materials for Steam Turbines – Material Problems

Principle of Operation of Turbine Generator – Electricity Generation

Most nuclear power plants operate a single-shaft turbine-generator that consists of one multi-stage HP turbine and three parallel multi-stage LP turbines, the main generator and an exciter. HP Turbine is usually a double-flow impulse turbine (or reaction type) with about 10 stages with shrouded blades and produces about 30-40% of the gross power output of the power plant unit. LP turbines are usually double-flow reaction turbines with about 5-8 stages (with shrouded blades and free-standing blades of the last 3 stages). LP turbines produce approximately 60-70% of the gross power output of the power plant unit. Each turbine rotor is mounted on two bearings, i.e., there are double bearings between each turbine module.

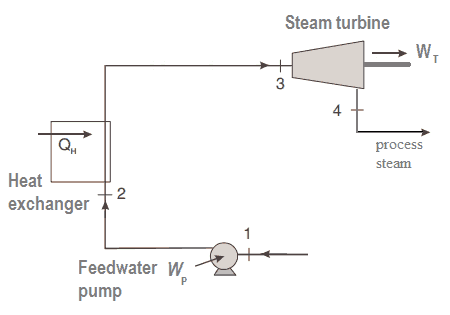

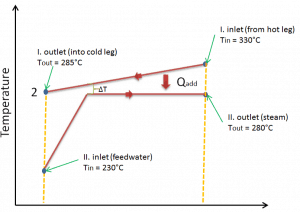

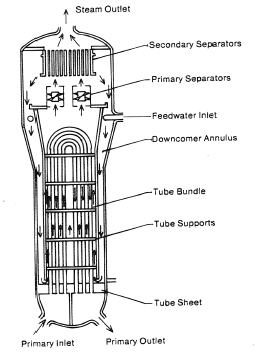

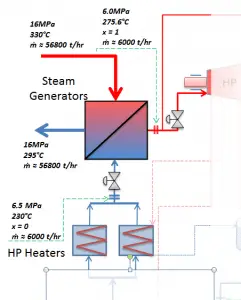

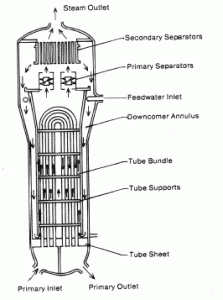

From Steam Generator to Main Steam Lines – Evaporation

The power conversion system of typical PWR begins in the steam generators in their shell sides. Steam generators are heat exchangers that convert feedwater into steam from heat produced in a nuclear reactor core. The feedwater (secondary circuit) is heated from ~230°C 500°F (preheated fluid by regenerators) to the boiling point of that fluid (280°C; 536°F; 6,5MPa). Heat is transferred through the walls of these tubes to the lower pressure secondary coolant located on the secondary side of the exchanger where the coolant evaporates to pressurized steam (saturated steam 280°C; 536°F; 6,5 MPa). The saturated steam leaves the steam generator through a steam outlet and continues to the main steam lines and further to the steam turbine.

These main steam lines are cross-tied (e.g.,, via steam collector pipe) near the turbine to ensure that the pressure difference between any steam generators does not exceed a specific value, thus maintaining system balance and ensuring uniform heat removal from the Reactor Coolant System (RCS). The steam flows through the main steam line isolation valves (MSIVs), which are very important to the high-pressure turbine from the safety point of view. Directly at the inlet of the steam turbine, there are throttle-stop valves and control valves. Turbine control is achieved by varying these turbine valves openings. In the event of a turbine trip, the steam supply must be isolated very quickly, usually in a fraction of a second, so the stop valves must operate quickly and reliably.

These main steam lines are cross-tied (e.g.,, via steam collector pipe) near the turbine to ensure that the pressure difference between any steam generators does not exceed a specific value, thus maintaining system balance and ensuring uniform heat removal from the Reactor Coolant System (RCS). The steam flows through the main steam line isolation valves (MSIVs), which are very important to the high-pressure turbine from the safety point of view. Directly at the inlet of the steam turbine, there are throttle-stop valves and control valves. Turbine control is achieved by varying these turbine valves openings. In the event of a turbine trip, the steam supply must be isolated very quickly, usually in a fraction of a second, so the stop valves must operate quickly and reliably.

From Turbine Valves to Condenser – Expansion

Typically most nuclear power plants operate multi-stage condensing steam turbines. In these turbines, the high-pressure stage receives steam (this steam is nearly saturated steam – x = 0.995 – point C at the figure; 6 MPa; 275.6°C) from a steam generator and exhausts it to moisture separator-reheater (MSR – point D). The steam must be reheated to avoid damages caused to the steam turbine blades by low-quality steam. The high content of water droplets can cause rapid impingement and erosion of the blades, which occurs when condensed water is blasted onto the blades. To prevent this, condensate drains are installed in the steam piping leading to the turbine.

The moisture-free steam is superheated by extraction steam from the high-pressure stage of the turbine and by steam directly from the main steam lines. The heating steam is condensed in the tubes and is drained to the feedwater system.

The reheater heats the steam (point D), and then the steam is directed to the low-pressure stage of the steam turbine, where it expands (point E to F). The exhausted steam then condenses in the condenser. It is at a pressure well below atmospheric (absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa) and is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%. The turbine’s high and low-pressure stages are usually on the same shaft to drive a common generator, but they have separate cases. The main generator produces electrical power, which is supplied to the electrical grid.

From Condenser to Condensate Pumps – Condensation

The main condenser condenses the exhaust steam from the main turbine’s low-pressure stages and the steam dump system. The exhausted steam is condensed by passing over tubes containing water from the cooling system.

The main condenser condenses the exhaust steam from the main turbine’s low-pressure stages and the steam dump system. The exhausted steam is condensed by passing over tubes containing water from the cooling system.

The pressure inside the condenser is given by the ambient air temperature (i.e., water temperature in the cooling system) and by steam ejectors or vacuum pumps, which pull the gases (non-condensable) from the surface condenser eject them to the atmosphere.

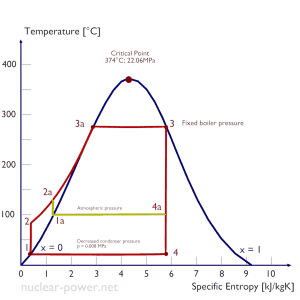

The lowest feasible condenser pressure is the saturation pressure corresponding to the ambient temperature (e.g.,, the absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa, which corresponds to 41.5°C). Note that there is always a temperature difference between (around ΔT = 14°C) the condenser temperature and the ambient temperature, which originates from condensers’ finite size and efficiency. Since neither the condenser is a 100% efficient heat exchanger, there is always a temperature difference between the saturation temperature (secondary side) and the temperature of the coolant in the cooling system. Moreover, there is design inefficiency, which decreases the overall efficiency of the turbine. Ideally, the steam exhausted into the condenser would have no subcooling. But real condensers are designed to subcool the liquid by a few degrees Celsius to avoid the suction cavitation in the condensate pumps. But, this subcooling increases the inefficiency of the cycle because more energy is needed to reheat the water.

The goal of maintaining the lowest practical turbine exhaust pressure is a primary reason for including the condenser in a thermal power plant. The condenser provides a vacuum that maximizes the energy extracted from the steam, resulting in a significant increase in network and thermal efficiency. But also this parameter (condenser pressure) has its engineering limits:

- Decreasing the turbine exhaust pressure decreases the vapor quality (or dryness fraction). At some point, the expansion must be ended to avoid damages caused to blades of steam turbine by low-quality steam.

- Decreasing the turbine exhaust pressure significantly increases the specific volume of exhausted steam, which requires huge blades in the last rows of the low-pressure stage of the steam turbine.

In a typical wet steam turbine, the exhausted steam condenses in the condenser, and it is at a pressure well below atmospheric (absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa, which corresponds to 41.5°C). This steam is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%. Note that the pressure inside the condenser is also dependent on the ambient atmospheric conditions:

- air temperature, pressure, and humidity in case of cooling into the atmosphere

- water temperature and the flow rate in case of cooling into a river or sea

An increase in the ambient temperature causes a proportional increase in pressure of exhausted steam (ΔT = 14°C is usually a constant); hence the thermal efficiency of the power conversion system decreases. In other words, the electrical output of a power plant may vary with ambient conditions, while the thermal power remains constant.

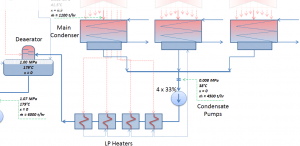

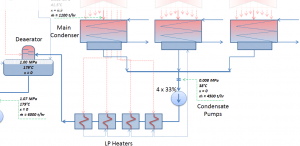

The condensed steam (now called condensate) is collected in the condenser’s hotwell. Condenser’s hotwell also provides a water storage capacity required for operational purposes such as feedwater makeup. The condensate (saturated or slightly subcooled liquid) is delivered to the condensate pump and then pumped by condensate pumps to the deaerator through a feedwater heating system. The condensate pumps increase the pressure usually to about p = 1-2 MPa. There are usually four one-third-capacity centrifugal condensate pumps with common suction and discharge headers. Three pumps are normally in operation, with one in the backup.

From Condensate Pumps to Feedwater Pumps – Heat Regeneration

The condensate from condensate pumps then passes through several stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters. The temperature of the condensate is increased by heat transfer from steam extracted from the low-pressure turbines. There are usually three or four stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters connected in the cascade. The condensate exits the low-pressure feedwater heaters at approximately p = 1 MPa, t = 150°C, entering the deaerator. The main condensate system also contains a mechanical condensate purification system for removing impurities. The feedwater heaters are self-regulating. It means that the greater the flow of feedwater, the greater the rate of heat absorption from the steam and the greater the flow of extraction steam.

The condensate from condensate pumps then passes through several stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters. The temperature of the condensate is increased by heat transfer from steam extracted from the low-pressure turbines. There are usually three or four stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters connected in the cascade. The condensate exits the low-pressure feedwater heaters at approximately p = 1 MPa, t = 150°C, entering the deaerator. The main condensate system also contains a mechanical condensate purification system for removing impurities. The feedwater heaters are self-regulating. It means that the greater the flow of feedwater, the greater the rate of heat absorption from the steam and the greater the flow of extraction steam.

There are non-return valves in the extraction steam lines between the feedwater heaters and the turbine. These non-return valves prevent the reverse steam or water flow in case of turbine trip, which causes a rapid decrease in the pressure inside the turbine. Any water entering the turbine in this way could cause severe damage to the turbine blading.

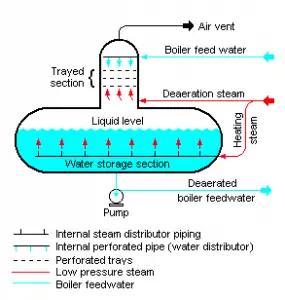

Deaerator

In general, a deaerator is a device used to remove oxygen and other dissolved gases from the feedwater to steam generators. The deaerator is part of the feedwater heating system. It is usually situated between the last low-pressure heater and feedwater booster pumps. In particular, dissolved oxygen in the steam generator can cause serious corrosion damage by attaching to the walls of metal piping and other metallic equipment and forming oxides (rust). Furthermore, dissolved carbon dioxide combines with water to form carbonic acid that causes further corrosion.

The condensate is heated to saturated conditions in the deaerator, usually by the steam extracted from the steam turbine. The extraction steam is mixed in the deaerator by a system of spray nozzles and cascading trays between which the steam percolates. Any dissolved gases in the condensate are released in this process and removed from the deaerator by venting to the atmosphere or the main condenser. Directly below the deaerator is the feedwater storage tank, in which a large quantity of feedwater is stored at near saturation conditions. This feedwater can be supplied to steam generators to maintain the required water inventory during the transient in the turbine trip event. The deaerator and storage tank are usually located at a high elevation in the turbine hall to ensure an adequate net positive suction head (NPSH) to the feedwater pumps at the inlet. NPSH is used to measure how close a fluid is too saturated conditions. Lowering the pressure at the suction side can induce cavitation. This arrangement minimizes the risk of cavitation in the pump.

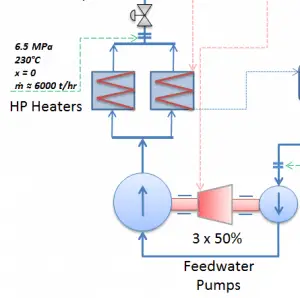

From Feedwater Pumps to Steam Generator

The system of feedwater pumps usually contains three parallel lines (3×50%) of feedwater pumps with common suction and discharge headers. Each feedwater pump consists of the booster and the main feedwater pump. The feed water pumps (usually driven by steam turbines) increase the pressure of the condensate (~1MPa) to the pressure in the steam generator (~6.5MPa).

The system of feedwater pumps usually contains three parallel lines (3×50%) of feedwater pumps with common suction and discharge headers. Each feedwater pump consists of the booster and the main feedwater pump. The feed water pumps (usually driven by steam turbines) increase the pressure of the condensate (~1MPa) to the pressure in the steam generator (~6.5MPa).

The booster pumps provide the required main feedwater pump suction pressure. These pumps (both feedwater pumps) are normally high-pressure pumps (usually of the centrifugal pump type) that take suction from the deaerator water storage tank, which is mounted directly below the deaerator, and supply the main feedwater pumps. The water discharge from the feedwater pumps flows through the high-pressure feedwater heaters, enters the containment, and then flows into the steam generators.

Feedwater flow to each steam generator is controlled by feedwater regulating valves (FRVs) in each feedwater line. The regulator is controlled automatically by steam generator level, steam flow, and feedwater flow.

The high-pressure feedwater heaters are heated by extraction steam from the high-pressure turbine, HP Turbine. Drains from the high-pressure feedwater heaters are usually routed to the deaerator.

The feedwater (water 230°C; 446°F; 6,5MPa) is pumped into the steam generator through the feedwater inlet. In the steam generator is the feedwater (secondary circuit) heated from ~230°C 446°F to the boiling point of that fluid (280°C; 536°F; 6,5MPa). Feedwater is then evaporated, and the pressurized steam (saturated steam 280°C; 536°F; 6,5 MPa) leaves the steam generator through the steam outlet and continues to the steam turbine, thereby completing the cycle.