Let assume the ideal Brayton cycle that describes the workings of a constant pressure heat engine. Modern gas turbine engines and airbreathing jet engines also follow the Brayton cycle.

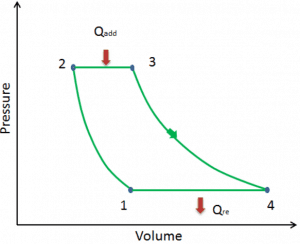

The ideal Brayton cycle consists of four thermodynamic processes. Two isentropic processes and two isobaric processes.

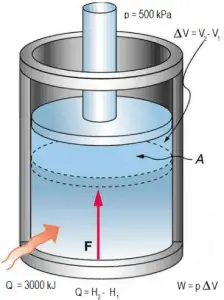

- Isentropic compression – ambient air is drawn into the compressor, pressurized (1 → 2). The work required for the compressor is given by WC = H2 – H1.

- Isobaric heat addition – the compressed air then runs through a combustion chamber, burning fuel, and air or another medium is heated (2 → 3). It is a constant-pressure process since the chamber is open to flow in and out. The net heat added is given by Qadd = H3 – H2

- Isentropic expansion – the heated, pressurized air then expands on a turbine, gives up its energy. The work done by the turbine is given by WT = H4 – H3

- Isobaric heat rejection – the residual heat must be rejected to close the cycle. The net heat rejected is given by Qre = H4 – H1

Assume an isobaric heat addition (2 → 3) in a heat exchanger. In typical gas turbines, the high-pressure stage receives gas (point 3 at the figure; p3 = 6.7 MPa; T3 = 1190 K (917°C)) from a heat exchanger. Moreover, we know that the compressor receives gas (point 1 at the figure; p1 = 2.78 MPa; T1 = 299 K (26°C)), and we know that the isentropic efficiency of the compressor is ηK = 0.87 (87%).

Calculate the heat added by the heat exchanger (between 2 → 3).

Solution:

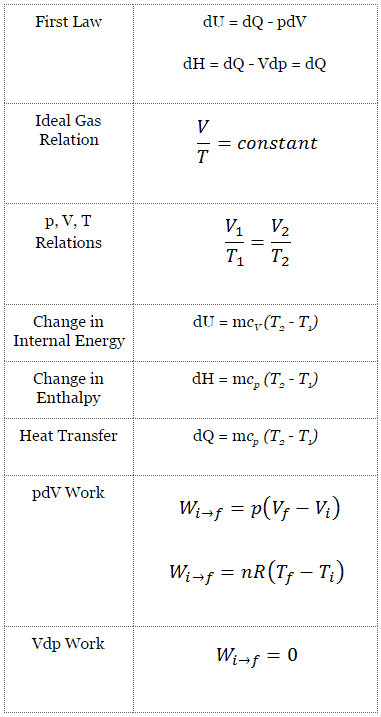

From the first law of thermodynamics, the net heat added is given by Qadd = H3 – H2 or Qadd = Cp.(T3-T2s), but we do not know the temperature (T2s) at the outlet of the compressor. We will solve this problem in intensive variables. We have to rewrite the previous equation (to include ηK) using the term (+h1 – h1) to:

Qadd = h3 – h2 = h3 – h1 – (h2s – h1)/ηK

Qadd = cp(T3-T1) – (cp(T2s-T1)/ηK)

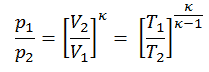

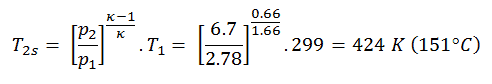

Then we will calculate the temperature, T2s, using p, V, T Relation for the adiabatic process between (1 → 2).

In this equation, the factor for helium is equal to =cp/cv=1.66. The previous equation follows that the compressor outlet temperature, T2s, is:

From Ideal Gas Law we know, that the molar specific heat of a monatomic ideal gas is:

Cv = 3/2R = 12.5 J/mol K and Cp = Cv + R = 5/2R = 20.8 J/mol K

We transfer the specific heat capacities into units of J/kg K via:

cp = Cp . 1/M (molar weight of helium) = 20.8 x 4.10-3 = 5200 J/kg K

Using this temperature and the isentropic compressor efficiency we can calculate the heat added by the heat exchanger:

Qadd = cp(T3-T1) – (cp(T2s-T1)/ηK) = 5200.(1190 – 299) – 5200.(424-299)/0.87 = 4.633 MJ/kg – 0.747 MJ/kg = 3.886 MJ/kg