Since there are changes in internal energy (dU) and changes in system volume (∆V), engineers often use the enthalpy of the system, which is defined as:

H = U + pV

In many thermodynamic analyses, it is convenient to use enthalpy instead of internal energy, especially in the first law of thermodynamics.

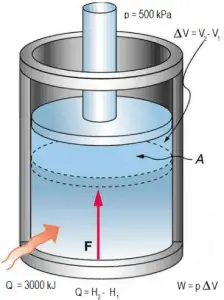

The enthalpy is the preferred expression of system energy that changes in many chemical, biological, and physical measurements at constant pressure. It is so useful that it is tabulated in the steam tables along with specific volume and specific internal energy. It is due to the fact and it simplifies the description of energy transfer. At constant pressure, the enthalpy change equals the energy transferred from the environment through heating (Q = H2 – H1) or work other than expansion work. For a variable-pressure process, the difference in enthalpy is not quite as obvious.

There are expressions in terms of more familiar variables such as temperature and pressure:

dH = CpdT + V(1-αT)dp

Where Cp is the heat capacity at constant pressure and α is the (cubic) thermal expansion coefficient. For ideal gas αT = 1 and therefore:

dH = CpdT

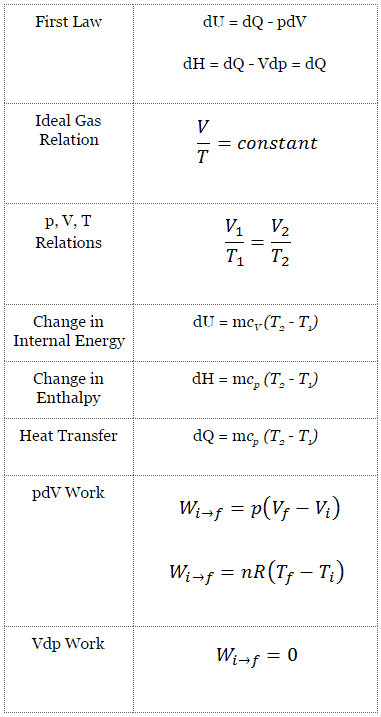

The case n = 0 corresponds to an isobaric (constant-pressure) process for an ideal gas and a polytropic process. In contrast to the adiabatic process, in which n = and a system exchanges no heat with its surroundings (Q = 0; ∆T≠0), in an isobaric process, there is a change in the internal energy (due to ∆T≠0) and therefore ΔU ≠ 0 (for ideal gases) and Q ≠ 0.

In engineering, both important thermodynamic cycles (Brayton and Rankine cycle) are based on two isobaric processes. Therefore the study of this process is crucial for power plants.

Isobaric Process and the First Law

The classical form of the first law of thermodynamics is the following equation:

dU = dQ – dW

In this equation, dW is equal to dW = pdV and is known as the boundary work.

In an isobaric process and the ideal gas, part of the heat added to the system will be used to do work, and part of the heat added will increase the internal energy (increase the temperature). Therefore it is convenient to use enthalpy instead of internal energy.Since H = U + pV, therefore dH = dU + pdV + Vdp and we substitute dU = dH – pdV – Vdp into the classical form of the law:

dH – pdV – Vdp = dQ – pdV

We obtain the law in terms of enthalpy:

dH = dQ + Vdp

or

dH = TdS + Vdp

In this equation, the term Vdp is a flow process work. This work, Vdp, is used for open flow systems like a turbine or a pump in which there is a “dp”, i.e., change in pressure. There are no changes in the control volume. As can be seen, this form of the law simplifies the description of energy transfer. At constant pressure, the enthalpy change equals the energy transferred from the environment through heating:

Isobaric process (Vdp = 0):

dH = dQ → Q = H2 – H1

At constant entropy, i.e., in the isentropic process, the enthalpy change equals the flow process work done on or by the system.

Isentropic process (dQ = 0):

dH = Vdp → W = H2 – H1

It is obvious, and it will be very useful in the analysis of both thermodynamic cycles used in power engineering, i.e., in the Brayton and Rankine cycles.

Isobaric Process – Ideal Gas Equation

See also: What is an Ideal Gas

Let assume an isobaric heat addition in an ideal gas. In an ideal gas, molecules have no volume and do not interact. According to the ideal gas law, pressure varies linearly with temperature and quantity and inversely with volume.

pV = nRT

where:

- p is the absolute pressure of the gas

- n is the amount of substance

- T is the absolute temperature

- V is the volume

- R is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant,

In this equation, the symbol R is a constant called the universal gas constant that has the same value for all gases—namely, R = 8.31 J/mol K.

The isobaric process can be expressed with the ideal gas law as:

or

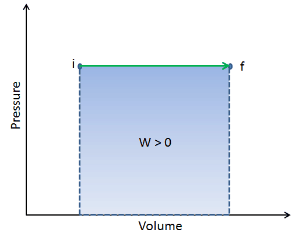

On a p-V diagram, the process occurs along a horizontal line (called an isobar) with the equation p = constant.

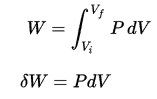

Pressure-volume work by the closed system is defined as:

Assuming that the quantity of ideal gas remains constant and applying the ideal gas law, this becomes

According to the ideal gas model, the internal energy can be calculated by:

∆U = m cv ∆T

where the property cv (J/mol K) is referred to as specific heat (or heat capacity) at a constant volume because under certain special conditions (constant volume), it relates the temperature change of a system to the amount of energy added by heat transfer.

Adding these equations together, we obtain the equation for heat:

Q = m cv ∆T + m R ∆T = m (cv +R)∆T = m cp ∆T

where the property cp (J/mol K) is referred to as specific heat (or heat capacity) constant pressure.

See also: Specific Heat at Constant Volume and Constant Pressure

See also: Mayer’s formula

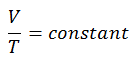

Charles’s Law

Charles’s Law is one of the gas laws. At the end of the 18th century, a French inventor and scientist, Jacques Alexandre César Charles, studied the relationship between the volume and the temperature of a gas at constant pressure. Certain experiments with gases at relatively low pressure led Jacques Alexandre César Charles to formulate a well-known law. It states that:

The volume is directly proportional to the Kelvin temperature for a fixed mass of gas at constant pressure.

That means that, for example, if you double the temperature, you will double the volume. If you halve the temperature, you will halve the volume.

You can express this mathematically as:

V = constant . T

Yes, it seems to be identical to the isobaric process of an ideal gas. These results are fully consistent with the ideal gas law, which determinates that the constant is equal to nR/p. If you rearrange the pV = nRT equation by dividing both sides by p, you will obtain:

V = nR/p . T

where nR/p is constant and:

- p is the absolute pressure of the gas

- n is the amount of substance

- T is the absolute temperature

- V is the volume

- R is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant,

In this equation, the symbol R is a constant called the universal gas constant that has the same value for all gases—namely, R = 8.31 J/mol K.

Example of Isobaric Process – Isobaric Heat Addition

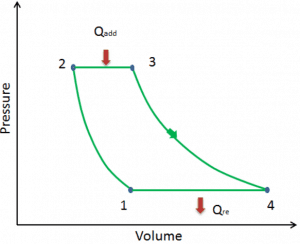

Let assume the ideal Brayton cycle that describes the workings of a constant pressure heat engine. Modern gas turbine engines and airbreathing jet engines also follow the Brayton cycle.

The ideal Brayton cycle consists of four thermodynamic processes. Two isentropic processes and two isobaric processes.

- Isentropic compression – ambient air is drawn into the compressor, pressurized (1 → 2). The work required for the compressor is given by WC = H2 – H1.

- Isobaric heat addition – the compressed air then runs through a combustion chamber, burning fuel, and air or another medium is heated (2 → 3). It is a constant-pressure process since the chamber is open to flow in and out. The net heat added is given by Qadd = H3 – H2

- Isentropic expansion – the heated, pressurized air then expands on a turbine, gives up its energy. The work done by the turbine is given by WT = H4 – H3

- Isobaric heat rejection – the residual heat must be rejected to close the cycle. The net heat rejected is given by Qre = H4 – H1

Assume an isobaric heat addition (2 → 3) in a heat exchanger. In typical gas turbines, the high-pressure stage receives gas (point 3 at the figure; p3 = 6.7 MPa; T3 = 1190 K (917°C)) from a heat exchanger. Moreover, we know that the compressor receives gas (point 1 at the figure; p1 = 2.78 MPa; T1 = 299 K (26°C)), and we know that the isentropic efficiency of the compressor is ηK = 0.87 (87%).

Calculate the heat added by the heat exchanger (between 2 → 3).

Solution:

From the first law of thermodynamics, the net heat added is given by Qadd = H3 – H2 or Qadd = Cp.(T3-T2s), but we do not know the temperature (T2s) at the outlet of the compressor. We will solve this problem in intensive variables. We have to rewrite the previous equation (to include ηK) using the term (+h1 – h1) to:

Qadd = h3 – h2 = h3 – h1 – (h2s – h1)/ηK

Qadd = cp(T3-T1) – (cp(T2s-T1)/ηK)

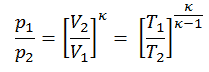

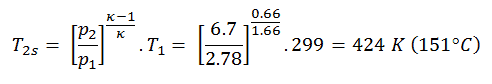

Then we will calculate the temperature, T2s, using p, V, T Relation for the adiabatic process between (1 → 2).

In this equation, the factor for helium is equal to =cp/cv=1.66. The previous equation follows that the compressor outlet temperature, T2s, is:

From Ideal Gas Law we know, that the molar specific heat of a monatomic ideal gas is:

Cv = 3/2R = 12.5 J/mol K and Cp = Cv + R = 5/2R = 20.8 J/mol K

We transfer the specific heat capacities into units of J/kg K via:

cp = Cp . 1/M (molar weight of helium) = 20.8 x 4.10-3 = 5200 J/kg K

Using this temperature and the isentropic compressor efficiency we can calculate the heat added by the heat exchanger:

Qadd = cp(T3-T1) – (cp(T2s-T1)/ηK) = 5200.(1190 – 299) – 5200.(424-299)/0.87 = 4.633 MJ/kg – 0.747 MJ/kg = 3.886 MJ/kg