pΔV Work

Pressure-volume work (or pΔV Work) occurs when the volume V of a system changes. The pΔV Work is equal to the area under the process curve plotted on the pressure-volume diagram. It is also known as boundary work. Boundary work occurs because the mass of the substance within the system boundary causes a force, the pressure times the surface area, to act on the boundary surface and move it. Boundary work (or pΔV Work) occurs when the volume V of a system changes. It is used for calculating piston displacement work in a closed system. This happens when steam or gas contained in a piston-cylinder device expands against the piston and forces the piston to move.

Example:

Consider a frictionless piston that is used to provide a constant pressure of 500 kPa in a cylinder containing steam (superheated steam) of a volume of 2 m3 at 500 K.

Calculate the final temperature if 3000 kJ of heat is added.

Solution:

Using steam tables we know, that the specific enthalpy of such steam (500 kPa; 500 K) is about 2912 kJ/kg. Since the steam has a density of 2.2 kg/m3, we know about 4.4 kg of steam in the piston at an enthalpy of 2912 kJ/kg x 4.4 kg = 12812 kJ.

When we use simply Q = H2 − H1, then the resulting enthalpy of steam will be:

H2 = H1 + Q = 15812 kJ

From steam tables, such superheated steam (15812/4.4 = 3593 kJ/kg) will have a temperature of 828 K (555°C). Since at this enthalpy, the steam has a density of 1.31 kg/m3, it is obvious that it has expanded by about 2.2/1.31 = 1.67 (+67%). Therefore the resulting volume is 2 m3 x 1.67 = 3.34 m3 and ∆V = 3.34 m3 – 2 m3 = 1.34 m3.

The p∆V part of enthalpy, i.e., the work done is:

W = p∆V = 500 000 Pa x 1.34 m3 = 670 kJ

———–

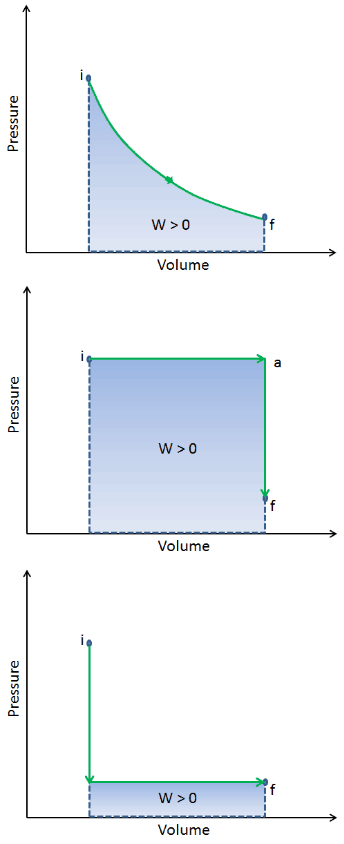

During the volume change, the pressure and temperature may also change. To calculate such processes, we would need to know how pressure varies with volume for the actual process by which the system changes from state i to state f. The first law of thermodynamics and the work can then be expressed as:

When a thermodynamic system changes from an initial state to a final state, it passes through a series of intermediate states. We call this series of states a path. There are always infinitely many different possibilities for these intermediate states. When they are all equilibrium states, the path can be plotted on a pV-diagram. One of the most important conclusions is that:

The work done by the system depends not only on the initial and final states but also on the intermediate states—that is, on the path.

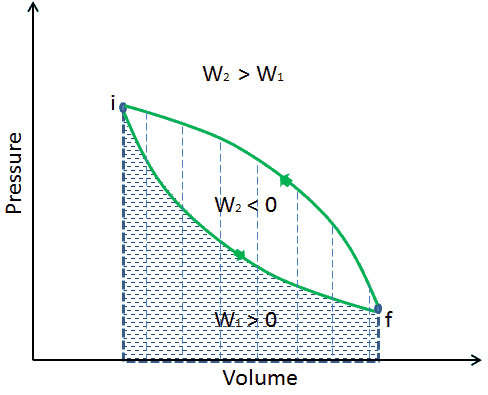

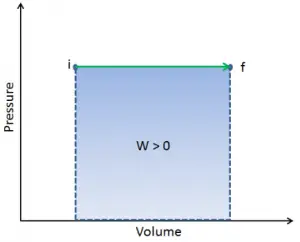

Q and W are path-dependent, whereas ΔEint is path-independent. As can be seen from the picture (p-V diagram), work is a path-dependent variable. The blue area represents the pΔV Work done by a system from an initial state i to a final state f. Work W is positive because the system’s volume increases. The second process shows that work is greater, and that depends on the path of the process.

Moreover, we can take the system through a series of states forming a closed loop, such i ⇒ f ⇒ i. In this case, the final state is the same as the initial state, but the total work done by the system is not zero. A positive value for work indicates that work is done by the system in its surroundings. A negative value indicates that work is done on the system by its surroundings.

First Law in Terms of Enthalpy dH = dQ + Vdp

The enthalpy is defined to be the sum of the internal energy E plus the product of the pressure p and volume V. In many thermodynamic analyses, the sum of the internal energy U and the product of pressure p and volume V appears. Therefore it is convenient to give the combination a name, enthalpy, and a distinct symbol, H.

H = U + pV

See also: Enthalpy

The first law of thermodynamics in terms of enthalpy shows us why engineers use the enthalpy in thermodynamic cycles (e.g.,, Brayton cycle or Rankine cycle).

The classical form of the law is the following equation:

dU = dQ – dW

In this equation dW is equal to dW = pdV and is known as the boundary work.

dH – pdV – Vdp = dQ – pdV

We obtain the law in terms of enthalpy:

dH = dQ + Vdp

or

dH = TdS + Vdp

In this equation, the term Vdp is a flow process work. This work, Vdp, is used for open flow systems like a turbine or a pump in which there is a “dp”, i.e., change in pressure. There are no changes in the control volume. As can be seen, this form of the law simplifies the description of energy transfer. At constant pressure, the enthalpy change equals the energy transferred from the environment through heating:

Isobaric process (Vdp = 0):

dH = dQ → Q = H2 – H1

At constant entropy, i.e., in isentropic process, the enthalpy change equals the flow process work done on or by the system:

Isentropic process (dQ = 0):

dH = Vdp → W = H2 – H1

It is obvious, and it will be very useful in the analysis of both thermodynamic cycles used in power engineering, i.e., in the Brayton and Rankine cycles.