In thermodynamics, enthalpy is the measure of energy in a thermodynamic system. It is the thermodynamic quantity equivalent to the total heat content of a system. The enthalpy is the preferred expression of system energy changes in chemical, biological, and physical measurements at constant pressure. It is so useful that it is tabulated in the steam tables along with specific volume and specific internal energy. It is due to the fact and it simplifies the description of energy transfer. At constant pressure, the enthalpy change equals the energy transferred from the environment through heating (Q = H2 – H1) or work other than expansion work. For a variable-pressure process, the difference in enthalpy is not quite as obvious.

Enthalpy in Extensive Units

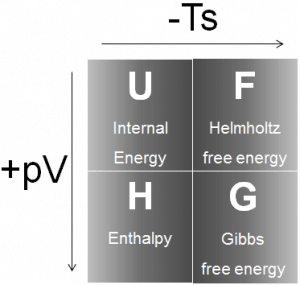

H = U + pV

Enthalpy is an extensive quantity. It depends on the size of the system or on the amount of substance it contains. The SI unit of enthalpy is the joule (J). It is the energy contained within the system, excluding the kinetic energy of motion of the system as a whole and the potential energy of the system as a whole due to external force fields. It is the thermodynamic quantity equivalent to the total heat content of a system.

On the other hand, energy can be stored in the chemical bonds between the atoms that make up the molecules. This energy storage on the atomic level includes energy associated with electron orbital states, nuclear spin, and binding forces in the nucleus.

Enthalpy is represented by the symbol H, and the change in enthalpy in a process is H2 – H1.

There are expressions in terms of more familiar variables such as temperature and pressure:

dH = CpdT + V(1-αT)dp

Where Cp is the heat capacity at constant pressure and α is the (cubic) thermal expansion coefficient. For ideal gas αT = 1 and therefore:

dH = CpdT

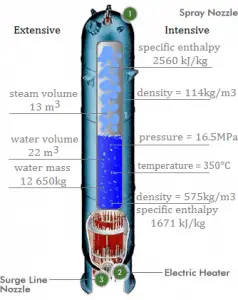

Specific Enthalpy

The enthalpy can be made into an intensive or specific variable by dividing by the mass. Engineers use the specific enthalpy in thermodynamic analysis more than the enthalpy itself. The specific enthalpy (h) of a substance is its enthalpy per unit mass. It equals the total enthalpy (H) divided by the total mass (m).

h = H/m

where:

h = specific enthalpy (J/kg)

H = enthalpy (J)

m = mass (kg)

Note that enthalpy is the thermodynamic quantity equivalent to the total heat content of a system. The specific enthalpy is equal to the specific internal energy of the system plus the product of pressure and specific volume.

h = u + pv

In general, enthalpy is a property of a substance, like pressure, temperature, and volume, but it cannot be measured directly. Normally, the enthalpy of a substance is given for some reference value. For example, the specific enthalpy of water or steam is given using the reference that the specific enthalpy of water is zero at 0.01°C and normal atmospheric pressure, where hL = 0.00 kJ/kg. The absolute value of specific enthalpy is unknown is not a problem, however, because it is the change in specific enthalpy (∆h) and not the absolute value that is important in practical problems.

Enthalpy in Chemical Reactions

The enthalpy is also widely used in chemistry. Chemical reactions are determined by the laws of thermodynamics. In thermodynamics, the internal energy of a system is the energy contained within the system, excluding the kinetic energy of motion of the system as a whole and the potential energy of the system as a whole due to external force fields. The enthalpy of a chemical reaction is defined as the enthalpy change observed in a constituent of a thermodynamic system when one mole of substance reacts completely.

Since most of the chemical reactions in a laboratory are constant-pressure processes, we can write the change in enthalpy (also known as enthalpy of reaction) for a reaction. The enthalpy of reaction can be positive or negative or zero depending upon whether the heat is gained or lost or no heat is lost or gained. In an endothermic reaction, the products have more stored chemical energy than the reactants. In an exothermic reaction, the opposite is true. The products have less stored chemical energy than the reactants. The excess energy is generally released to the surroundings when the reaction occurs.

In chemical reactions, energy is stored in the chemical bonds between the atoms that make up the molecules. Energy storage on the atomic level includes energy associated with electron orbital states. Whether a chemical reaction absorbs or releases energy, there is no overall change in the amount of energy during the reaction. That’s because of the law of conservation of energy, which states that:

Energy cannot be created or destroyed. Energy may change form during a chemical reaction.

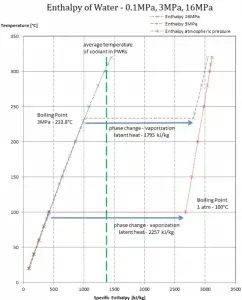

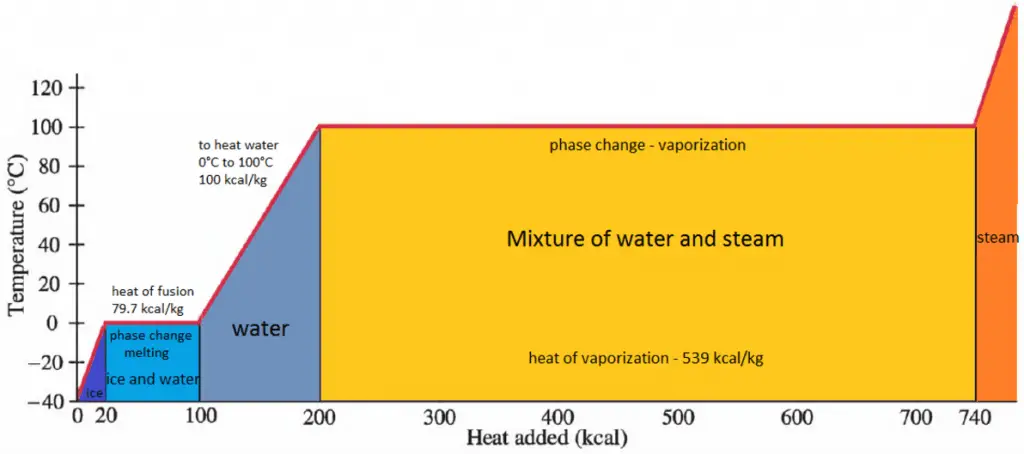

Enthalpy of Vaporization

In general, when a material changes phase from solid to liquid or from liquid to gas, a certain amount of energy is involved in this change of phase. In the case of liquid to gas phase change, this amount of energy is the enthalpy of vaporization (symbol ∆Hvap; unit: J), also known as the (latent) heat of vaporization or heat of evaporation. Latent heat is the amount of heat added to or removed from a substance to produce a phase change. This energy breaks down the intermolecular attractive forces and must provide the energy necessary to expand the gas (the pΔV work). When latent heat is added, no temperature change occurs. The enthalpy of vaporization is a function of the pressure at which that transformation takes place.

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 0.1 MPa (atmospheric pressure)

hlg = 2257 kJ/kg

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 3 MPa (pressure inside a steam generator)

hlg = 1795 kJ/kg

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 16 MPa (pressure inside a pressurizer)

hlg = 931 kJ/kg

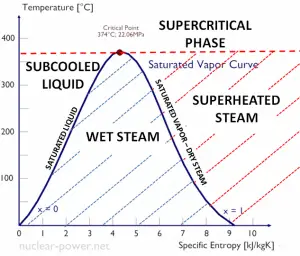

The heat of vaporization diminishes with increasing pressure while the boiling point increases. It vanishes completely at a certain point called the critical point. Above the critical point, the liquid and vapor phases are indistinguishable, and the substance is called a supercritical fluid.

The heat of vaporization is the heat required to completely vaporize a unit of saturated liquid (or condense a unit mass of saturated vapor). It is equal to hlg = hg − hl.

The heat necessary to melt (or freeze) a unit mass at the substance at constant pressure is the heat of fusion and is equal to hsl = hl − hs, where hs is the enthalpy of saturated solid and hl is the enthalpy of saturated liquid.

Specific Enthalpy of Wet Steam

The specific enthalpy of saturated liquid water (x=0) and dry steam (x=1) can be picked from steam tables. In the case of wet steam, the actual enthalpy can be calculated with the vapor quality, x, and the specific enthalpies of saturated liquid water and dry steam:

The specific enthalpy of saturated liquid water (x=0) and dry steam (x=1) can be picked from steam tables. In the case of wet steam, the actual enthalpy can be calculated with the vapor quality, x, and the specific enthalpies of saturated liquid water and dry steam:

hwet = hs x + (1 – x ) hl

where

hwet = enthalpy of wet steam (J/kg)

hs = enthalpy of “dry” steam (J/kg)

hl = enthalpy of saturated liquid water (J/kg)

As can be seen, wet steam will always have lower enthalpy than dry steam.

Example:

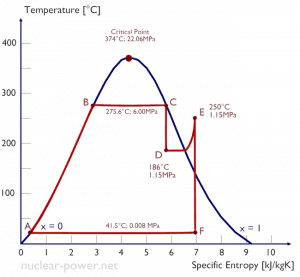

A high-pressure steam turbine stage operates at a steady state with inlet conditions of 6 MPa, t = 275.6°C, x = 1 (point C). Steam leaves this turbine stage at a pressure of 1.15 MPa, 186°C, and x = 0.87 (point D). Calculate the enthalpy difference between these two states.

The enthalpy for the state C can be picked directly from steam tables, whereas the enthalpy for the state D must be calculated using vapor quality:

h1, wet = 2785 kJ/kg

h2, wet = h2,s x + (1 – x ) h2,l = 2782 . 0.87 + (1 – 0.87) . 790 = 2420 + 103 = 2523 kJ/kg

Δh = 262 kJ/kg

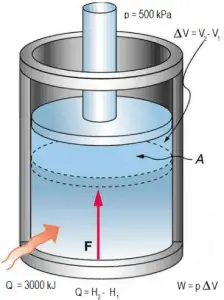

Example: Frictionless Piston – Heat – Enthalpy

A frictionless piston is used to provide a constant pressure of 500 kPa in a cylinder containing steam (superheated steam) of a volume of 2 m3 at 500 K. Calculate the final temperature if 3000 kJ of heat is added.

Solution:

Using steam tables we know, that the specific enthalpy of such steam (500 kPa; 500 K) is about 2912 kJ/kg. Since in this condition, the steam has a density of 2.2 kg/m3, we know there is about 4.4 kg of steam in the piston at enthalpy of 2912 kJ/kg x 4.4 kg = 12812 kJ.

When we use simply Q = H2 − H1, then the resulting enthalpy of steam will be:

H2 = H1 + Q = 15812 kJ

From steam tables, such superheated steam (15812/4.4 = 3593 kJ/kg) will have a temperature of 828 K (555°C). Since at this enthalpy, the steam has a density of 1.31 kg/m3, it is obvious that it has expanded by about 2.2/1.31 = 1.67 (+67%). Therefore the resulting volume is 2 m3 x 1.67 = 3.34 m3 and ∆V = 3.34 m3 – 2 m3 = 1.34 m3.

The p∆V part of enthalpy, i.e., the work done, is:

W = p∆V = 500 000 Pa x 1.34 m3 = 670 kJ

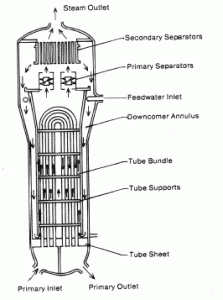

Example: Energy Balance in a Steam Generator

Calculate the amount of primary coolant, which is required to evaporate 1 kg of feedwater in a typical steam generator. Assume that there are no energy losses. This is only an idealized example.

Balance of the primary circuit

The hot primary coolant (water 330°C; 626°F; 16MPa) is pumped into the steam generator through the primary inlet. The primary coolant leaves (water 295°C; 563°F; 16MPa) the steam generator through the primary outlet.

hI, inlet = 1516 kJ/kg

=> ΔhI = -206 kJ/kg

hI, outlet = 1310 kJ/kg

Balance of the feedwater

The feedwater (water 230°C; 446°F; 6,5MPa) is pumped into the steam generator through the feedwater inlet. The feedwater (secondary circuit) is heated from ~230°C 446°F to the boiling point of that fluid (280°C; 536°F; 6,5MPa). Feedwater is then evaporated, and the pressurized steam (saturated steam 280°C; 536°F; 6,5 MPa) leaves the steam generator through the steam outlet and continues to the steam turbine.

hII, inlet = 991 kJ/kg

=> ΔhII = 1789 kJ/kg

hII, outlet = 2780 kJ/kg

Balance of the steam generator

Since the difference in specific enthalpies is less for primary coolant than for feedwater, it is obvious that the amount of primary coolant will be higher than 1kg. To produce 1 kg of saturated steam from feedwater, about 1789/206 x 1 kg = 8.68 kg of primary coolant is required.

Enthalpy of Nuclear Fuel – Acceptance Criteria

As was written, enthalpy is one of the thermodynamic potentials and represents a measure of energy in a thermodynamic system.

Enthalpy is an extensive quantity. It depends on the size of the system or on the amount of substance it contains.

H = U + pV

Enthalpy of nuclear fuel is also an acceptance criterion in specific types of accidents, known as reactivity-initiated accidents (RIA), such as Rod Ejection Accidents. RIAs consist of postulated accidents that involve a sudden and rapid insertion of positive reactivity. As a result of rapid power excursion, fuel temperatures rapidly increase, prompting fuel pellet thermal expansion. The power excursion is initially mitigated by the fuel temperature coefficient (or Doppler feedback), the first feedback that will compensate for the inserted positive reactivity.

In these accidents, the large and rapid deposition of energy in the fuel can result in melting, fragmentation, and dispersal. The mechanical action associated with fuel dispersal can be sufficient to destroy the cladding and the rod-bundle geometry of the fuel and produce pressure pulses in the primary system. The expulsion of hot fuel into the water can cause rapid steam generation and these pressure pulses, damaging nearby fuel assemblies. Limits on specific fuel enthalpy are used because the experimental tests show that the degree of fuel rod damage correlates well with the peak value of fuel pellet specific enthalpy.

Regulatory acceptance criteria vary with country and reactor type, but there are usually two kinds of fuel enthalpy limits:

- CORE COOL-ABILITY CRITERIA. Reduction of cool-ability can result from violent expulsion of fuel, which could damage nearby fuel assemblies. In the past, the core cool-ability criteria were revised to address short-term (e.g.,, fuel-to-coolant interaction, rod burst) and long-term (e.g.,, fuel rod ballooning, flow blockage) phenomena that challenge cool-able geometry and reactor pressure boundary integrity. A definite limit for core damage, which must not be exceeded at any position in any fuel rod in the core. According to Appendix B of the Standard Review Plan, Section 4.2, these criteria are, for example:

- Peak radial average fuel enthalpy must remain below 230 cal/g. Above this enthalpy, hot fuel particles might be expelled from a fuel rod.

- Peak fuel temperature must remain below incipient fuel melting conditions.

- FUEL CLADDING FAILURE CRITERIA. A fuel rod failure threshold defines whether a fuel rod should be considered failed or not in calculations of radioactive release (source term). According to Appendix B of the Standard Review Plan, Section 4.2 fuel rods may fail by several damage mechanisms:

- The high cladding temperature failure criteria for zero power conditions is a peak radial average fuel enthalpy greater than 170 cal/g for fuel rods with an internal rod pressure at or below system pressure and 150 cal/g for fuel rods with an internal rod pressure exceeding system pressure.

- The PCMI failure criteria change radial average fuel enthalpy greater than the corrosion-dependent limit depicted in Appendix B of the Standard Review Plan, Section 4.2.

As can be seen, the fuel-specific enthalpy, i.e., the enthalpy per unit mass of the fuel pellet material, is, therefore, a fundamental parameter in discussions of reactivity-initiated accidents. Fuel cladding failure may occur almost instantaneously during the prompt fuel enthalpy rise (due to PCMI) or may occur as total fuel enthalpy (prompt + delayed), heat flux, and cladding temperature increase. The prompt fuel enthalpy rise is defined as the radial average fuel enthalpy rise at the time corresponding to one pulse width after the peak of the prompt pulse to calculate fuel enthalpy for assessing PCMI failures. The total radial average fuel enthalpy (prompt + delayed) should be used to assess high cladding temperature failures.

Special Reference: US NRC. Standard Review Plan – NUREG-0800. 4.2 FUEL SYSTEM DESIGN. Revision 3 – March 2007.

Special Reference: OECD Nuclear Energy Agency State-of-the-art Report, “Nuclear Fuel Behaviour under RIA Conditions”, 2010.

Special Reference: Peter Rudling, Lars Olof Jernkvist. Nuclear Fuel Behaviour under RIA Conditions. Advanced Nuclear Technology International, 12/2016.