It is known the fission neutrons are of importance in any chain-reacting system. Neutrons trigger the nuclear fission of some nuclei (235U, 238U, or even 232Th). What is crucial the fission of such nuclei produces 2, 3, or more free neutrons.

But not all neutrons are released at the same time following fission. Even the nature of the creation of these neutrons is different. From this point of view, we usually divide the fission neutrons into two following groups:

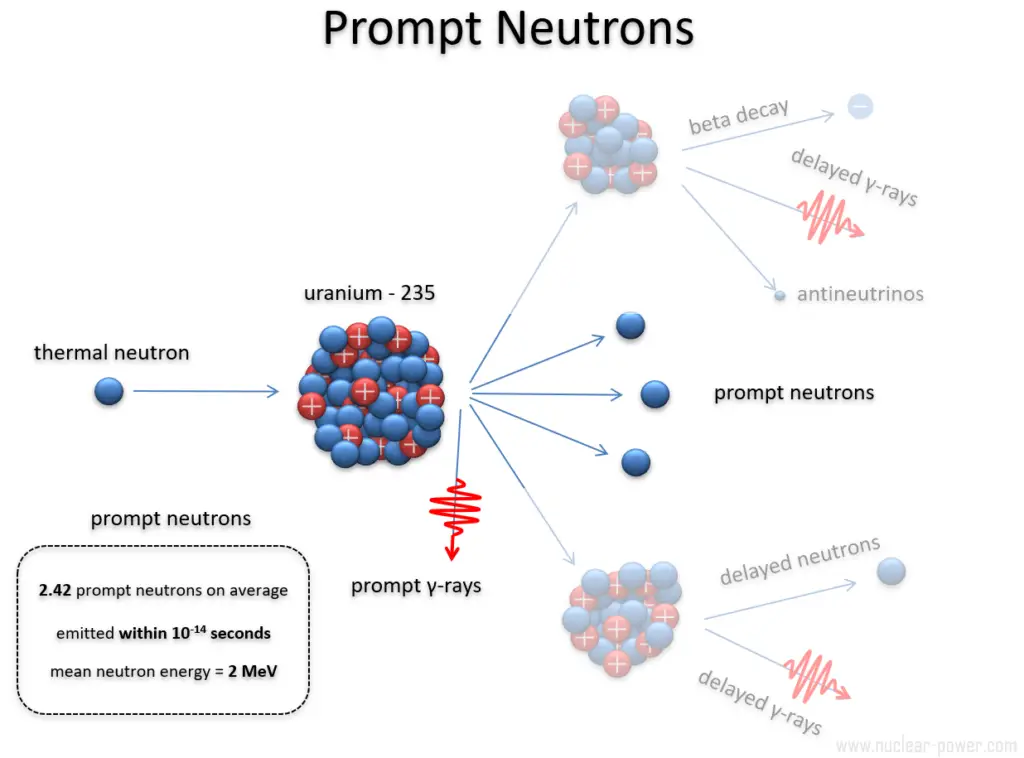

Prompt Neutrons. Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission, and they are emitted within a very short time of about 10-14 seconds.

Prompt Neutrons. Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission, and they are emitted within a very short time of about 10-14 seconds.- Delayed Neutrons. Delayed neutrons are emitted by neutron-rich fission fragments that are called delayed neutron precursors. These precursors usually undergo beta decay, but a small fraction of them are excited enough to undergo neutron emission. The neutron is produced via this type of decay, which happens orders of magnitude later than the emission of the prompt neutrons, which plays an extremely important role in controlling the reactor.

Prompt Neutrons

Prompt fission neutrons and prompt gamma rays are emitted when excited primary fission fragments release their energy to reach a more stable configuration. This happens shortly after the fission of the nucleus on two fission fragments. Studying prompt neutrons and gamma rays is important for deepening our understanding of the nuclear fission process and core design calculations or radiation shielding calculations.

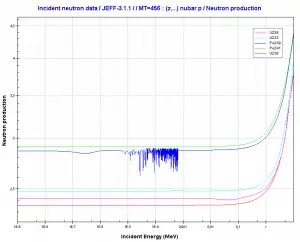

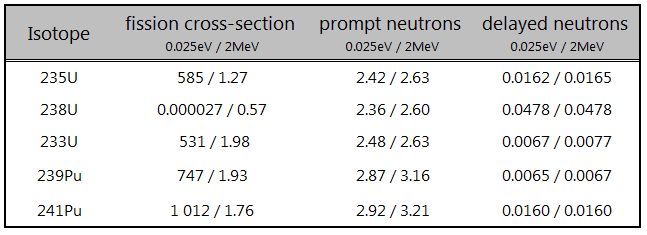

Most of the neutrons produced in fission are prompt neutrons. Usually, more than 99 percent of the fission neutrons are prompt neutrons. Still, the exact fraction is dependent on the nuclide to be fissioned and is also dependent on an incident neutron energy (usually increases with energy). For example, fission of 235U by thermal neutron yields 2.43 neutrons, of which 2.42 neutrons are the prompt neutrons, and 0.01585 neutrons (0.01585/2.43=0.0065=ß) are the delayed neutrons. The production of prompt neutrons slightly increases with incident neutron energy.

Prompt neutrons are emitted within 10-14 seconds. This is very important because it is very, very fast and causes a very fast response of the reactor power in case of prompt criticality. Therefore nuclear reactors must operate in a prompt subcritical, delayed critical condition. All power reactors are designed to operate in delayed critical conditions and are provided with safety systems to prevent them from ever achieving prompt criticality.

The reactor’s response on the reactivity insertion is determined by a neutron generation time (not by emission time), which is the average time from a prompt neutron emission to a capture that results only in fission.

Key Characteristics of Prompt Neutrons

- Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission, and they are emitted within a very short time of about 10-14 seconds.

- Most of the neutrons produced in fission are prompt neutrons – about 99.9%.

- For example, fission of 235U by thermal neutron yields 2.43 neutrons, of which 2.42 neutrons are prompt neutrons, and 0.01585 neutrons are the delayed neutrons.

- The production of prompt neutrons slightly increases with incident neutron energy.

- Almost all prompt fission neutrons have energies between 0.1 MeV and 10 MeV.

- The mean neutron energy is about 2 MeV. The most probable neutron energy is about 0.7 MeV.

- In reactor design, the prompt neutron lifetime (PNL) belongs to key neutron-physical characteristics of the reactor core.

- Its value depends especially on the type of the moderator and the energy of the neutrons causing fission.

- In an infinite reactor (without escape), prompt neutron lifetime is the sum of the slowing downtime and the diffusion time.

- In LWRs, the PNL increases with the fuel burnup.

- The typical prompt neutron lifetime in thermal reactors is on the order of 10-4 seconds.

- The typical prompt neutron lifetime in fast reactors is on the order of 10-7 seconds.

Prompt Gamma Rays

With the prompt neutrons, prompt gamma rays are associated. Most prompt gamma rays are emitted after prompt neutrons. The fission reaction releases approximately ~7 MeV in prompt gamma rays and an additional ~7 MeV (for 235U) in delayed gamma rays. This is a significant portion of energy (~7 % of fission energy released), and it must be considered in many fields of reactor design or the design of nuclear reactor shields. A particular challenge is the calculation of the gamma heat deposition in core baffles (reflectors), pressure vessels, or excore detector channels.

Comparing various benchmarks experiments with calculated gamma heating showed a systematic underestimation for the main fuel isotopes 235U and 239Pu. Discrepancies observed for C/E ratios in various benchmarks range from 10 to 28%, while the required accuracy is 7.5%. Therefore requests for new measurements of prompt gamma-rays in the reactions 235U(n,f) and 239Pu(n,f) have been formulated in the Nuclear Data High Priority Request List of the Nuclear Energy Agency.

Prompt Neutron Lifetime

Prompt neutron lifetime, l, is the average time from a prompt neutron emission to its absorption (fission or radiative capture) or its escape from the system. This parameter is defined in multiplying or also in non-multiplying systems. In both systems the prompt neutron lifetimes depend strongly on:

- the material composition of the system

- multiplying – non-multiplying system

- a system with or without thermalization

- isotopic composition of the system

- the geometric configuration of the system

- homogeneous or heterogeneous system

- the shape of the entire system

- size of the system

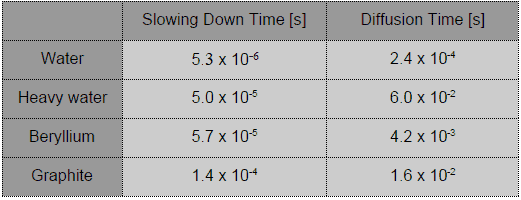

In an infinite reactor (without escape), prompt neutron lifetime is the sum of the slowing downtime and the diffusion time.

l=ts + td

In an infinite thermal reactor ts << td and therefore l ≈ td. The typical prompt neutron lifetime in thermal reactors is on the order of 10−4 seconds. Generally, the longer neutron lifetimes occur in systems where the neutrons must be thermalized to be absorbed.

Most neutrons are absorbed in higher energies, and the neutron thermalization is suppressed (e.g.,, in fast reactors) has much shorter prompt neutron lifetimes. The typical prompt neutron lifetime in fast reactors is on the order of 10−7 seconds.

Slowing Down and Diffusion Times for Thermal Neutrons in an Infinite Medium

Source: Robert Reed Burn, Introduction to Nuclear Reactor Operation, 1988.

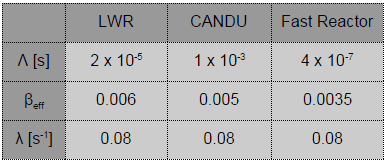

Prompt Generation Time – Mean Generation Time

In multiplying systems, the absorption of a prompt fission neutron can initiate a fission reaction, l is equal to the average time between two generations of prompt neutrons (at keff=1). This time is known as the prompt neutron generation time.

Prompt Neutron Generation Time (or Mean Generation Time), Λ, is the average time from a prompt neutron emission to a capture that results only in fission. The prompt neutron generation time is designated as:

Prompt Neutron Generation Time (or Mean Generation Time), Λ, is the average time from a prompt neutron emission to a capture that results only in fission. The prompt neutron generation time is designated as:

Λ = l/keff

In power reactors, the prompt generation time changes with the fuel burnup. In LWRs increases with the fuel burnup. It is simple. Fresh uranium fuel contains much fissile material (in the case of uranium fuel, about 4% of 235U). This causes significant excess of reactivity, and this excess must be compensated via chemical shim (in case of PWRs) or burnable absorbers.

Due to these factors (high probability of absorption in fuel and high probability of absorption in moderator), the prompt neutron lives much shorter, and the prompt neutron lifetime is low. With fuel burnup, the amount of fissile material and the absorption in the moderator decreases, and therefore the prompt neutron can “live” much longer.

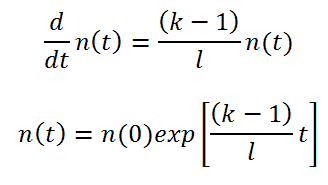

Example – Infinite Multiplying System Without Source and Delayed Neutrons

An equation governing the neutron kinetics of the system without source and with the absence of delayed neutrons is the point kinetics equation (in a certain form). This equation states that the time change of the neutron population is equal to the excess of neutron production (by fission) minus neutron loss by absorption in one prompt neutron lifetime. The role of prompt neutron lifetime is evident. Shorter lifetimes give simply faster responses to multiplying systems.

If there are neutrons in the system at t=0, that is, if n(0) > 0, the solution of this equation gives the simplest form of point kinetics equation (without source and delayed neutrons):

Let us consider that the prompt neutron lifetime is ~2 x 10-5, and k (k∞ – neutron multiplication factor) will be increased by only 0.01% (i.e., 10pcm or ~1.5 cents). That is, k∞=1.0000 will increase to k∞=1.0001.

It must be noted such reactivity insertion (10pcm) is very small in case of LWRs. The reactivity insertions of the order of one pcm are for LWRs practically unrealizable. In this case the reactor period will be:

T = l / (k∞ – 1) = 2 x 10-5 / (1.0001 – 1) = 0.2s

This is a very short period. In one second, the reactor’s neutron flux (and power) would increase by a factor of e5 = 2.7185. In 10 seconds, the reactor would pass through 50 periods, and the power would increase by e50 = ……

Furthermore, in the case of fast reactors in which prompt neutron lifetimes are of the order of 10-7 seconds, the response of such a small reactivity insertion will be even more unimaginable. In the case of 10-7, the period will be:

T = l / (k∞ – 1) = 10-7 / (1.0001 – 1) = 0.001s

Reactors with such kinetics would be very difficult to control. Fortunately, this behavior is not observed in any multiplying system. Actual reactor periods are observed to be considerably longer than computed above, and therefore the nuclear chain reaction can be controlled more easily. The longer periods are observed due to the presence of the delayed neutrons.

Interactive chart – Infinite Multiplying System Without Source and Delayed Neutrons

Press the “clear and run” button and try to stabilize the power at 90%.

Look at the reactivity insertion you need to insert to stabilize the system (of the order to a tenth of pcm).

Do you think that such a system is controllable?

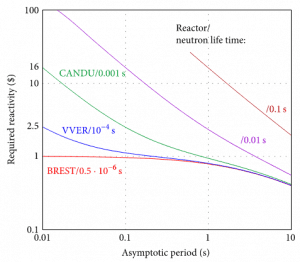

Effect of Prompt Neutron Lifetime on Nuclear Safety

The prompt neutron lifetime belongs to key neutron-physical characteristics of the reactor core. Its value depends especially on the type of the moderator and the energy of the neutrons causing fission. Its importance for nuclear reactor safety has been well known for a long time.

The longer prompt neutron lifetimes can substantially improve the kinetic response of the reactor (the longer prompt neutron lifetime gives simply a slower power increase). For example, under RIA conditions (Reactivity-Initiated Accidents), reactors should withstand a jump-like insertion of relatively large (~1 $ or even more) positive reactivity, and the PNL (prompt neutron lifetime) plays here the key role. Therefore the PNL should be verified in a reload safety evaluation process.

In some cases (especially in some fast reactors), reactor cores can be modified to increase the PNL and improve nuclear safety.

See also: Improving Nuclear Safety of Fast Reactors by Slowing Down Fission Chain Reaction.

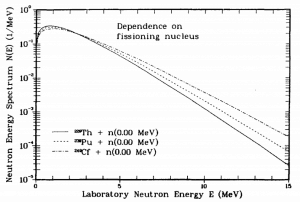

Prompt Neutron Energy Spectrum

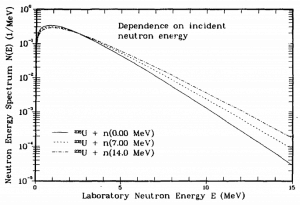

Studying prompt neutron energy spectra is important in many nuclear reactor applications (e.g.,, criticality calculations) and constitutes the most important component of the source term for nuclear reactor shielding calculations.

Basic features of prompt neutron energy spectra are summarized below:

- The neutrons produced by fission are high-energy neutrons.

- Almost all fission neutrons have energies between 0.1 MeV and 10 MeV.

- The prompt neutron energy distribution, or spectrum, maybe best described by the dependence of the fraction of neutrons per MeV on neutron energy.

- The most probable neutron energy is about 0.7 MeV.

The mean neutron energy is about 2 MeV. - These values are for thermal fission of 235U, but these values vary only slightly for other nuclides.

Prompt neutron fission spectra evaluation is one of the most interesting aspects of the evaluation of actinides. Many experimental and theoretical researches have been carried out for the determination of prompt neutron spectra. There are several representations of prompt fission neutron spectra. The Maxwellian and Watt spectrum are two early models of the prompt fission neutron spectrum, which are still used today.

The modern spectrum representation of the prompt fission neutron spectrum and average prompt neutron multiplicity is the Madland-Nix Spectrum (Los Alamos Model). This model is based upon the standard nuclear evaporation theory and utilizes an isospin-dependent optical potential for the inverse process of compound nucleus formation in neutron-rich fission fragments.

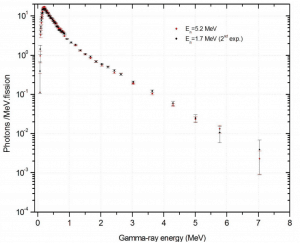

Prompt Neutron Energy Spectra – Dependence on fissioning nucleus.

Prompt Neutron Energy Spectra – Dependence on fissioning nucleus.

Source: Madland, David G., New Fission-Neutron-Spectrum Representation for ENDF, LA-9285-MS, April 1982. Prompt Neutron Energy Spectra – Dependence on incident neutron energy.

Prompt Neutron Energy Spectra – Dependence on incident neutron energy.

Source: Madland, David G., New Fission-Neutron-Spectrum Representation for ENDF, LA-9285-MS, April 1982.