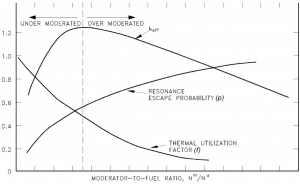

From the moderator-to-fuel ratio point of view, any multiplying system can be designed as:

- Under-moderated. Under-moderation means less than the optimum amount of moderator between fuel plates or fuel rods. An increase in moderator temperature and voids decreases the keff of the system and inserts negative reactivity. An under-moderated core would create a negative temperature and void feedback required for a stable system.

- Over-moderated. Over-moderation means a higher than optimum amount of moderator between fuel plates or fuel rods. An increase in moderator temperature and voids increases the keff of the system and inserts positive reactivity. An over-moderated core would create a positive temperature and void feedback. It will result in an unstable system unless another negative feedback mechanism (e.g., the Doppler broadening) overrides the positive effect.

Reactor engineers must balance the composite effects of moderator density, fuel temperature, and other phenomena to ensure system stability under all operating conditions. Most light water reactors are therefore designed as so-called under-moderated, and the neutron flux spectrum is slightly harder (the moderation is slightly insufficient) than in an optimum case. But this design provides an important safety feature. An increase in the moderator temperature results in negative reactivity, which tends to make the reactor self-regulating. It must be added the overall feedback must be negative. Still, local positive coefficients exist in areas with large water gaps that are over-moderated such as near control rods guide tubes.

Reactor engineers must balance the composite effects of moderator density, fuel temperature, and other phenomena to ensure system stability under all operating conditions. Most light water reactors are therefore designed as so-called under-moderated, and the neutron flux spectrum is slightly harder (the moderation is slightly insufficient) than in an optimum case. But this design provides an important safety feature. An increase in the moderator temperature results in negative reactivity, which tends to make the reactor self-regulating. It must be added the overall feedback must be negative. Still, local positive coefficients exist in areas with large water gaps that are over-moderated such as near control rods guide tubes.

Another phenomenon associated with an under-moderated core is called the neutron flux trap effect. This effect causes an increase in local power generation due to better thermalization of neutrons in areas with large water gaps (between fuel assemblies or when the fuel assembly bow phenomenon is present). Note that “flux traps” are a standard feature of most modern test reactors because of the desire to obtain high thermal neutron fluxes for the irradiation of materials. Still, it can also occur in PWRs.

On the other hand, also under-moderation has its limits. In general, it causes a decrease in overall keff. Therefore more fissile material is needed to ensure criticality of the core. Moreover, there is also a limit on the minimal value of MTC (most negative). It is because the negative temperature feedback also acts against a decrease in the moderator temperature. Consider what happens when moderator temperature is decreased quickly, as in the case of the main steamline break (MSLB – standard initiating event for PWRs). The steamline break causes the steam pressure the saturation temperature in the steam generators to fall rapidly. As a result of the falling saturation temperature in the steam generators, the moderator temperature will rapidly decrease. The rapid moderator temperature drop causes a positive reactivity insertion. The amount of reactivity inserted also depends on the magnitude of the MTC, and therefore it must be limited. The typical values for lower limit are MTC = -80 pcm/°C, but it is a plant-specific value limited in technical specifications.

Moderator-to-fuel Ratio

As was written, the moderator temperature coefficient is primarily a function of the moderator-to-fuel ratio (NH2O/NFuel ratio). The moderator-to-fuel ratio is the ratio of the number of moderator nuclei within the reactor core volume to the number of fuel nuclei. As the core temperature increases, fuel volume and number density remain essentially constant. The volume of moderator also remains constant, but the number density of moderator decreases with thermal expansion. As the moderator temperature increases, the ratio of the moderating atoms (molecules of water) decreases due to the thermal expansion of water (especially at 300°C; see: Density of Water). Its density simply and significantly decreases. This, in turn, causes hardening of neutron spectrum in the reactor core resulting in higher resonance absorption (lower p). The decreasing density of the moderator causes neutrons to stay at a higher energy for a longer period, which increases the probability of non-fission capture of these neutrons. This process is one of three processes that determine the moderator temperature coefficient (MTC). The second process is associated with the leakage probability of the neutrons and the third with the thermal utilization factor.

The moderator-to-fuel ratio strongly influences especially:

- Resonance escape probability. An increase in the moderator-to-fuel ratio causes an increase in resonance escape probability. As more moderator molecules are added relative to the number of fuel molecules, then it becomes easy for neutrons to slow down to thermal energies without encountering a resonance absorption at the resonance energies.

- Thermal utilization factor. An increase in the moderator-to-fuel ratio causes a decrease in the thermal utilization factor. The value of the thermal utilization factor is given by the ratio of the number of thermal neutrons absorbed in the fuel (all nuclides) to the number of thermal neutrons absorbed in all the material that makes up the core.

- Thermal and fast non-leakage probability. An increase in moderator-to-fuel ratio causes a decrease in migration length, which in turn causes an increase in non-leakage probability.

As can be seen from the figure, at low moderator-to-fuel ratios, the product of all the six factors (keff) is small because the resonance escape probability is small. At the optimal value of the moderator-to-fuel ratio, keff reaches its maximum value. This is the case of so-called “optimal moderation”. At large ratios, keff is again small because the thermal utilization factor is small.