In general, when two objects are brought into thermal contact, heat will flow between them until they come into equilibrium with each other. When a temperature difference does exist, heat flows spontaneously from the warmer system to the colder system.

While internal energy refers to the total energy of all the molecules within the object, heat is the amount of energy flowing spontaneously from one body to another due to their temperature difference. Heat is a form of energy, but it is energy in transit. Heat is not a property of a system. However, the transfer of energy as heat occurs at the molecular level due to a temperature difference.

Consider a block of metal at high temperatures that consist of atoms oscillating intensely around their average positions. At low temperatures, the atoms continue to oscillate but with less intensity. If a hotter block of metal is put in contact with a cooler block, the intensely oscillating atoms at the edge of the hotter block give off their kinetic energy to the less oscillating atoms at the edge of the cool block. In this case, there is energy transfer between these two blocks, and heat flows from the hotter to the cooler block by these random vibrations.

Consider a block of metal at high temperatures that consist of atoms oscillating intensely around their average positions. At low temperatures, the atoms continue to oscillate but with less intensity. If a hotter block of metal is put in contact with a cooler block, the intensely oscillating atoms at the edge of the hotter block give off their kinetic energy to the less oscillating atoms at the edge of the cool block. In this case, there is energy transfer between these two blocks, and heat flows from the hotter to the cooler block by these random vibrations.

In general, when two objects are brought into thermal contact, heat will flow between them until they come into equilibrium with each other. When a temperature difference does exist, heat flows spontaneously from the warmer system to the colder system. Heat transfer occurs by conduction or by thermal radiation. When the flow of heat stops, they are said to be at the same temperature. They are then said to be in thermal equilibrium.

As with work, the amount of heat transferred depends upon the path and not simply on the initial and final conditions of the system. There are actually many ways to take the gas from state i to state f.

Also, as with work, it is important to distinguish between heat added to a system from its surroundings and heat removed from a system to its surroundings. Q is positive for heat added to the system, so Q is negative if heat leaves the system. Because W in the equation is the work done by the system, then if work is done on the system, W will be negative, and Eint will increase.

The symbol q is sometimes used to indicate the heat added to or removed from a system per unit mass. It equals the total heat (Q) added or removed divided by the mass (m).

Distinguishing Temperature, Heat, and Internal Energy

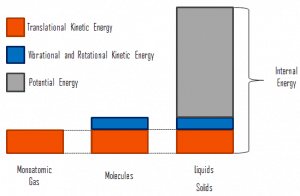

Using the kinetic theory, a clear distinction between these three properties can be made.

- Temperature is related to the kinetic energies of the molecules of a material. It is the average kinetic energy of individual molecules.

- Internal energy refers to the total energy of all the molecules within the object. Therefore, it is an extensive property when two equal-mass hot ingots of steel may have the same temperature, but two of them have twice as much internal energy as one does.

- Finally, heat is the amount of energy flowing spontaneously from one body to another due to their temperature difference.

It must be added, and when a temperature difference exists, heat flows spontaneously from the warmer to the colder system. Thus, if a 5 kg cube of steel at 100°C is placed in contact with a 500 kg cube of steel at 20°C, heat flows from the cube at 300°C to the cube at 20°C even though the internal energy of the 20°C cubes is much greater because there is so much more of it.

A particularly important concept is thermodynamic equilibrium. In general, when two objects are brought into thermal contact, heat will flow between them until they come into equilibrium with each other.

Heat Capacity

Different substances are affected to different magnitudes by the addition of heat. When a given amount of heat is added to different substances, their temperatures increase by different amounts. This proportionality constant between the heat Q that the object absorbs or loses and the resulting temperature change T of the object is known as the heat capacity C of an object.

Different substances are affected to different magnitudes by the addition of heat. When a given amount of heat is added to different substances, their temperatures increase by different amounts. This proportionality constant between the heat Q that the object absorbs or loses and the resulting temperature change T of the object is known as the heat capacity C of an object.

C = Q / ΔT

Heat capacity is an extensive property of matter, meaning it is proportional to the size of the system. Heat capacity C has the unit of energy per degree or energy per kelvin. When expressing the same phenomenon as an intensive property, the heat capacity is divided by the amount of substance, mass, or volume. Thus the quantity is independent of the size or extent of the sample.

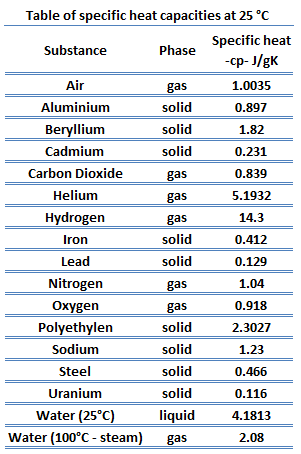

Specific Heat Capacity

The heat capacity of a substance per unit mass is called the substance’s specific heat capacity (cp). The subscript p indicates that the heat capacity and specific heat capacity apply when the heat is added or removed at constant pressure.

cp = Q / mΔT

Specific Heat Capacity

In the Ideal Gas Model, the intensive properties cv and cp are defined for pure, simple compressible substances as partial derivatives of the internal energy u(T, v) and enthalpy h(T, p), respectively:

where the subscripts v and p denote the variables held fixed during differentiation. The properties cv and cp are referred to as specific heats (or heat capacities). Under certain special conditions, they relate the temperature change of a system to the amount of energy added by heat transfer. Their SI units are J/kg K, or J/mol K. Two specific heats are defined for gases, constant volume (cv), and constant pressure (cp).

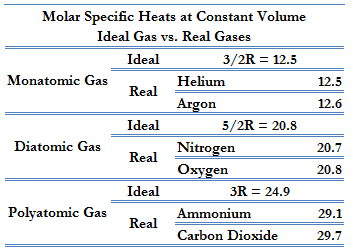

According to the first law of thermodynamics, for a constant volume process with a monatomic ideal gas, the molar specific heat will be:

According to the first law of thermodynamics, for a constant volume process with a monatomic ideal gas, the molar specific heat will be:

Cv = 3/2R = 12.5 J/mol K

because

U = 3/2nRT

It can be derived that the molar specific heat at constant pressure is:

Cp = Cv + R = 5/2R = 20.8 J/mol K

This Cp is greater than the molar specific heat at constant volume Cv because energy must now be supplied not only to raise the temperature of the gas but also for the gas to do work because, in this case, volume changes.

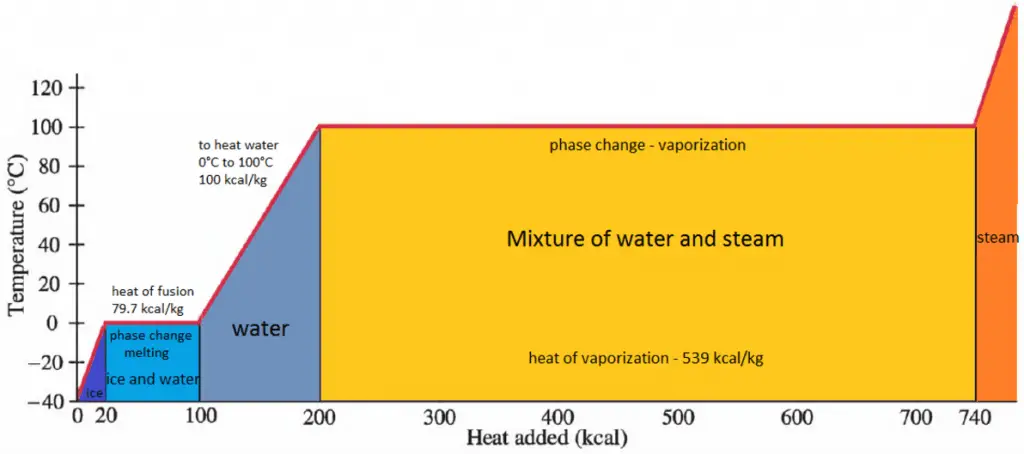

Latent Heat of Vaporization

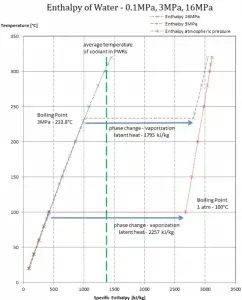

In general, when a material changes phase from solid to liquid or from liquid to gas, a certain amount of energy is involved in this change of phase. In the case of liquid to gas phase change, this amount of energy is the enthalpy of vaporization (symbol ∆Hvap; unit: J), also known as the (latent) heat of vaporization or heat of evaporation. Latent heat is the amount of heat added to or removed from a substance to produce a phase change. This energy breaks down the intermolecular attractive forces and must provide the energy necessary to expand the gas (the pΔV work). When latent heat is added, no temperature change occurs. The enthalpy of vaporization is a function of the pressure at which that transformation takes place.

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 0.1 MPa (atmospheric pressure)

hlg = 2257 kJ/kg

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 3 MPa (pressure inside a steam generator)

hlg = 1795 kJ/kg

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 16 MPa (pressure inside a pressurizer)

hlg = 931 kJ/kg

The heat of vaporization diminishes with increasing pressure, while the boiling point increases. It vanishes completely at a certain point called the critical point. Above the critical point, the liquid and vapor phases are indistinguishable, and the substance is called a supercritical fluid.

The heat of vaporization is the heat required to completely vaporize a unit of saturated liquid (or condense a unit mass of saturated vapor). It is equal to hlg = hg − hl.

The heat necessary to melt (or freeze) a unit mass at the substance at constant pressure is the heat of fusion and is equal to hsl = hl − hs, where hs is the enthalpy of saturated solid and hl is the enthalpy of saturated liquid.

Example – Evaporation of water at atmospheric pressure

Calculate heat required to evaporate 1 kg of water at the atmospheric pressure (p = 1.0133 bar) and the temperature of 100°C.

Solution:

Since these parameters correspond to the saturated liquid state, only latent heat of 1 kg of water vaporization is required. From steam tables, the latent heat of vaporization is L = 2257 kJ/kg. Therefore the heat required is equal to:

ΔH = 2257 kJ

Note that the initial specific enthalpy h1 = 419 kJ/kg, whereas the final specific enthalpy will be h2 = 2676 kJ/kg. The specific enthalpy of low-pressure dry steam is very similar to the specific enthalpy of high-pressure dry steam, despite having different temperatures.

Example – Evaporation of water at high pressure

Calculate heat required to evaporate 1 kg of feedwater at the pressure of 6 MPa (p = 60 bar) and the temperature of 275.6°C (saturation temperature).

Solution:

Since these parameters correspond to the saturated liquid state, only latent heat of 1 kg of water vaporization is required. From steam tables, the latent heat of vaporization is L = 1571 kJ/kg. Therefore the heat required is equal to:

ΔH = 1571 kJ

Note that the initial specific enthalpy h1 = 1214 kJ/kg, whereas the final specific enthalpy will be h2 = 2785 kJ/kg.