Surface Hardening – Case Hardening

Case hardening or surface hardening is the process in which the hardness of an object’s surface (case) is enhanced while the inner core of the object remains elastic and tough. After this process enhances surface hardness, wear resistance, and fatigue life. This is accomplished by several processes, such as a carburizing or nitriding process by which a component is exposed to a carbonaceous or nitrogenous atmosphere at elevated temperatures. As was written, two main material characteristics are influenced:

- Hardness and wear resistance is significantly enhanced. In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, abrasion, an indentation, or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

- Toughness is not negatively influenced, and toughness is the ability of a material to absorb energy and plastically deform without fracturing. One definition of toughness (for high-strain rate, fracture toughness) is that it is a property that is indicative of a material’s resistance to fracture when a crack (or other stress-concentrating defects) is present.

The case-hardening process involves infusing additional carbon or nitrogen into the surface layer for iron or steel with low carbon content, which has poor to no hardenability. Case hardening is useful in parts such as a cam or ring gear that must have a tough surface to resist wear and a tough interior to resist the impact that occurs during operation. Further, the surface hardening of steel has an advantage over through hardening (that is, hardening the metal uniformly throughout the piece) because less expensive low-carbon and medium-carbon steels can be surface hardened without the problems of distortion and cracking associated with the through hardening of thick sections. An atomic diffusion from the gaseous phase introduces a carbon- or nitrogen-rich outer surface layer (or case). The case is normally on the order of 1 mm deep and is harder than the inner core of the material.

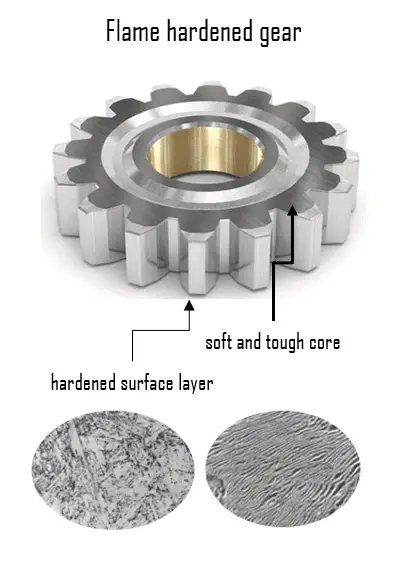

Flame Hardening

Flame hardening is a surface hardening technique that uses a single torch with a specially designed head to provide a very rapid means of heating the metal, which is then cooled rapidly, generally using water. This creates a “case” of martensite on the surface, while the inner core of the object remains elastic and tough. It is a similar technique to induction hardening. The carbon content of 0.3–0.6 wt% C is needed for this type of hardening.

Flame hardening is a surface hardening technique that uses a single torch with a specially designed head to provide a very rapid means of heating the metal, which is then cooled rapidly, generally using water. This creates a “case” of martensite on the surface, while the inner core of the object remains elastic and tough. It is a similar technique to induction hardening. The carbon content of 0.3–0.6 wt% C is needed for this type of hardening.

Martensite is a very hard metastable structure with a body-centered tetragonal (BCT) crystal structure. Martensite is formed in steels when austenite’s cooling rate is so high that carbon atoms do not have time to diffuse out of the crystal structure in large enough quantities to form cementite (Fe3C). Flame hardening produces hard, highly wear-resistant surface (deep case depths) with good capacity for contact load and good bending fatigue strength. It can be used for the hardening of low-cost steel, and low capital investment is required.

A common use for induction hardening is for hardening of large parts, such as gears and machine tool ways, with sizes or shapes that would make furnace heat treatment impractical. The gear will usually be quenched and tempered to a specific hardness first, making a majority of the gear tough. Then the teeth are quickly heated and immediately quenched, hardening only the surface. The wear resistance behavior of induction hardened parts depends on hardening depth and the magnitude and distribution of residual compressive stress in the surface layer.

Other Case Hardening Methods

Case hardening by surface treatment can be further classified as diffusion or localized heating treatments. Diffusion methods introduce alloying elements that enter the surface by diffusion, either as solid-solution agents or as hardenability agents that assist martensite formation during subsequent quenching. The alloying element concentration is increased at a steel component’s surface during this process. Diffusion methods include:

- Carburizing. Carburizing is a case hardening process in which the surface carbon concentration of a ferrous alloy (usually low-carbon steel) is increased by diffusion from the surrounding environment. Carburizing produces hard, highly wear-resistant surface (medium case depths) of product with an excellent capacity for contact load, good bending fatigue strength, and good resistance to seizure.

- Nitriding. Nitriding is a case hardening process in which the surface nitrogen concentration of a ferrous is increased by diffusion from the surrounding environment to create a case-hardened surface. Nitriding produces hard, highly wear-resistant surface (shallow case depths) of product with a fair capacity for contact load, good bending fatigue strength, and excellent resistance to seizure.

- Boriding. Boriding, also called boronizing, is a thermochemical diffusion process similar to nitrocarburizing in which boron atoms diffuse into the substrate to produce hard and wear-resistant surface layers. The process requires a high treatment temperature (1073-1323 K) and long duration (1-12 h) and can be applied to a wide range of materials such as steels, cast iron, cermets, and non-ferrous alloys.

- Titanium-carbon and Titanium-nitride Hardening. Titanium nitride (an extremely hard ceramic material) or titanium carbide coatings can be used in the tools made of this kind of steel through a physical vapor deposition process to improve the performance and life span of the tool. TiN has a Vickers hardness of 1800–2100 and a metallic gold color.

Localized heating methods for case hardening include:

- Flame hardening. Flame hardening is a surface hardening technique that uses a single torch with a specially designed head to provide a very rapid means of heating the metal, which is then cooled rapidly, generally using water. This creates a “case” of martensite on the surface while the inner core of the object remains elastic and rigid. It is a similar technique to induction hardening. The carbon content of 0.3–0.6 wt% C is needed for this type of hardening.

- Induction hardening. Induction hardening is a surface hardening technique that uses induction coils to provide a very rapid means of heating the metal, which is then cooled rapidly, generally using water. This creates a “case” of martensite on the surface. The carbon content of 0.3–0.6 wt% C is needed for this type of hardening.

- Laser hardening. Laser hardening is a surface hardening technique that uses a laser beam to provide a very rapid means of heating the metal, which is then cooled rapidly (generally by self-quenching). This creates a “case” of martensite on the surface while the inner core of the object remains elastic and rigid.