Superalloys, or high-performance alloys, are non-ferrous alloys that exhibit outstanding strength and surface stability at high temperatures. Their key characteristic is their ability to operate safely at a high fraction of their melting point (up to 85% of their melting points (Tm) expressed in degrees Kelvin, 0.85). Superalloys are generally used at temperatures above 540 °C (1000 °F); ordinary steel and titanium alloys lose their strength at these temperatures. Also, corrosion is common in steels at this temperature. At high temperatures, superalloys retain mechanical strength, resistance to thermal creep deformation, surface stability, and resistance to corrosion or oxidation. Some nickel-based superalloys can withstand temperatures beyond 1200°C, depending on the composition of the alloy. Superalloys are often cast as a single crystal. While grain boundaries may provide strength, they decrease creep resistance.

Superalloys, or high-performance alloys, are non-ferrous alloys that exhibit outstanding strength and surface stability at high temperatures. Their key characteristic is their ability to operate safely at a high fraction of their melting point (up to 85% of their melting points (Tm) expressed in degrees Kelvin, 0.85). Superalloys are generally used at temperatures above 540 °C (1000 °F); ordinary steel and titanium alloys lose their strength at these temperatures. Also, corrosion is common in steels at this temperature. At high temperatures, superalloys retain mechanical strength, resistance to thermal creep deformation, surface stability, and resistance to corrosion or oxidation. Some nickel-based superalloys can withstand temperatures beyond 1200°C, depending on the composition of the alloy. Superalloys are often cast as a single crystal. While grain boundaries may provide strength, they decrease creep resistance.

They were initially developed for use in aircraft piston engine turbosuperchargers. Today, the most common application is in aircraft turbine components, which must withstand exposure to severely oxidizing environments and high temperatures for reasonable periods. Current applications include:

- Aircraft gas turbines

- Steam turbine power plants

- Medical applications

- Space vehicles and rocket engines

- Heat-treating equipment

- Nuclear power plants

Nickel is the base element for superalloys, a group of nickel, iron-nickel, and cobalt alloys used in jet engines. These metals have excellent resistance to thermal creep deformation and retain their stiffness, strength, toughness, and dimensional stability at temperatures much higher than the other aerospace structural materials.

Types of Superalloys

Three main categories are jointly called superalloys, as mentioned below. They possess a high-temperature insensitivity or stability level and are widely used as base materials for high-temperature applications.

- Nickel-based Superalloys. Nickel-based superalloys currently constitute over 50% of the weight of advanced aircraft engines. Nickel-base superalloys include solid-solution-strengthened alloys and age-hardenable alloys. Age-hardenable alloys are austenitic (fcc) matrix dispersed with coherent precipitation of a Ni3(Al, Ti) intermetallic with an fcc structure. Ni-based superalloys are alloys with nickel as the primary alloying element and are preferred as blade material in the previously discussed applications, rather than Co- or Fe-based superalloys. Ni-based superalloys are significant for their high strength, creep, and corrosion resistance at high temperatures. It is common to cast turbine blades in directionally solidified or single-crystal forms. Single-crystal blades are mainly used in the first row in the turbine stage.

- Iron – Nickel-based Superalloys. Fe-based superalloys have shown creep and oxidation resistance similar to Ni-based superalloys while being far less expensive to produce. The most important class of this group are those alloys that are strengthened by intermetallic compound precipitation in an FCC matrix.

- Cobalt-based Superalloys. This class of alloys is relatively new. In 2006, Sato et al. discovered a new phase in the Co–Al–W system. Unlike other superalloys, cobalt-base alloys are characterized by a solid-solution-strengthened austenitic (fcc) matrix in which a small quantity of carbide is distributed. While not used commercially to the extent of Ni-based superalloys, alloying elements found in research Co-based alloys are C, Cr, W, Ni, Ti, Al, Ir, and Ta. They possess better weldability and thermal fatigue resistance as compared to nickel-based alloy. Moreover, their higher chromium contents have excellent corrosion resistance at high temperatures (980-1100 °C).

These alloys are generally used at temperatures above 450°C, as at these temperatures, ordinary steel and titanium alloys are losing their strengths. Also, corrosion is common in steels at this temperature.

Thermal Creep

Creep, also known as cold flow, is the permanent deformation that increases with time under constant load or stress. It results from long-time exposure to large external mechanical stress within the limit of yielding and is more severe in materials subjected to heat for a long time. The deformation rate is a function of the material’s properties, exposure time, exposure temperature, and the applied structural load. Creep is very important if we use materials at high temperatures. Creep is very important in the power industry and is of the highest importance in designing jet engines. Time to rupture is the dominant design consideration for many relatively short-life creep situations (e.g., turbine blades in military aircraft). Of course, for its determination, creep tests must be conducted to the point of failure, termed creep rupture tests.

The creep resistance of materials can be influenced by many factors such as diffusivity, precipitate, and grain size. In general, there are three general ways to prevent creep in metal. One way is to use higher melting point metals, the second is to use materials with greater grain size, and the third is to use alloying. Body-centered cubic (BCC) metals are less creep resistant in high temperatures. Therefore, superalloys (typically face-centered cubic austenitic alloys) based on Co, Ni, and Fe can be engineered to be highly resistant to creep and have thus arisen as an ideal material in high-temperature environments.

Inconel 718 – Nickel-based Superalloy

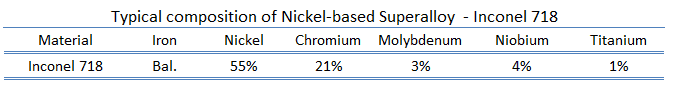

Inconel is a registered trademark of Special Metals for a family of austenitic nickel-chromium-based superalloys. Inconel 718 is a nickel-based superalloy with high strength properties and resistance to elevated temperatures, and it also demonstrates remarkable protection against corrosion and oxidation. Inconel’s high-temperature strength is developed by solid solution strengthening or precipitation hardening, depending on the alloy. Inconel 718 comprises 55% nickel, 21% chromium, 6% iron, and small amounts of manganese, carbon, and copper.

Common uses of superalloys are in the aerospace and some other high-technology industries. With the combination of corrosion resistance and material strength in the face of extreme heat, this kind of superalloy works well in the nuclear industry. Some nuclear plants use nickel-based superalloys for the reactor core, control rod, and similar parts. Low-cobalt superalloys (due to possible activation of cobalt-59) are used in the nuclear industry. Some structural parts of nuclear fuel assemblies, such as top and bottom nozzle, may be produced from superalloys such as Inconel. Spacing grids are usually made of corrosion-resistant material with a low absorption cross section for thermal neutrons, zirconium alloy (~ 0.18 × 10–24 cm2). The first and last spacing grid may also be made of low-cobalt Inconel, a superalloy well suited for service in extreme environments subjected to pressure and heat.

Stress-corrosion cracking

One of the most serious metallurgical problems and a major concern in the nuclear industry is stress-corrosion cracking (SCC). Stress-corrosion cracking results from the combined action of applied tensile stress and a corrosive environment, and both influences are necessary. SCC is a type of intergranular attack corrosion that occurs at the grain boundaries under tensile stress. Low alloy steels are less susceptible than high alloy steels but are subject to SCC in water containing chloride ions. Nickel-based alloys, however, are not effected by chloride or hydroxide ions. An example of a nickel-based alloy resistant to stress-corrosion cracking is Inconel.

Properties of Superalloy – Inconel 718

Material properties are intensive properties, which means they are independent of the amount of mass and may vary from place to place within the system at any moment. Materials science involves studying materials’ structure and relating them to their properties (mechanical, electrical, etc.). Once materials scientist knows about this structure-property correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a material in a given application. The major determinants of the structure of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical elements and how it has been processed into its final form.

Mechanical Properties of Superalloy – Inconel 718

Materials are frequently chosen for various applications because they have desirable combinations of mechanical characteristics. For structural applications, material properties are crucial, and engineers must consider them.

Strength of Superalloy – Inconel 718

In the mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. The strength of materials considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. The strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

The ultimate tensile strength of superalloy – Inconel 718 depends on the heat treatment process, but it is about 1200 MPa.

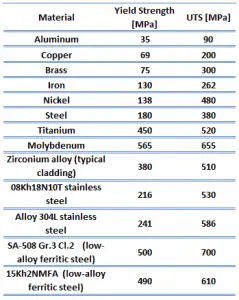

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the specimen preparation, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the specimen preparation, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

Yield Strength

The yield strength of superalloy – Inconel 718 depends on the heat treatment process, but it is about 1030 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically. In contrast, the yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Before the yield point, the material will deform elastically and return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behavior termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for high-strength steel.

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

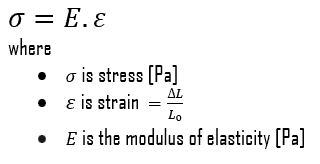

Young’s modulus of elasticity of superalloy – Inconel 718 is 200 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on the removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position, and all the atoms are displaced the same amount and maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions, and no permanent deformation occurs. According to Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.

The hardness of Superalloy – Inconel 718

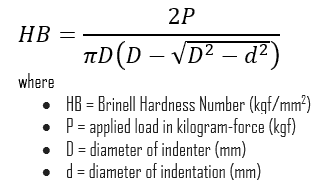

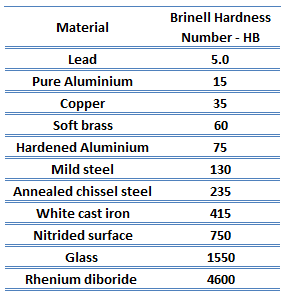

Brinell hardness of superalloy – Inconel 718 depends on the heat treatment process, but it is approximately 330 MPa.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, abrasion, indentation, or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, abrasion, indentation, or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

Brinell hardness test is one of the indentation hardness tests developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from Brinell, and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards, HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are various test methods in common use (e.g., Brinell, Knoop, Vickers, and Rockwell). Some tables correlate the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

Thermal Properties of Superalloy – Inconel 718

Thermal properties of materials refer to the response of materials to changes in their temperature and the application of heat. As a solid absorbs energy in the form of heat, its temperature rises, and its dimensions increase. But different materials react to the application of heat differently.

Heat capacity, thermal expansion, and thermal conductivity are often critical in solids’ practical use.

Melting Point of Superalloy – Inconel 718

The melting point of superalloy – Inconel 718 steel is around 1400°C.

In general, melting is a phase change of a substance from the solid to the liquid phase. The melting point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change occurs. The melting point also defines a condition where the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium.

Thermal Conductivity of Superalloy – Inconel 718

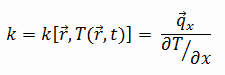

The thermal conductivity of superalloy – Inconel 718 is 6.5 W/(m. K).

The heat transfer characteristics of solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It measures a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies to all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas). Therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature, and for vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are nearly homogeneous. Therefore we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz). However, for an isotropic material, the thermal conductivity is independent of the transfer direction, kx = ky = kz = k.

Costs of Superalloys – Price

It isn’t easy to know the exact cost of the different materials because it strongly depends on many variables such as:

- the type of product you would like to buy

- the amount of the product

- the exact type of material

Raw materials prices change daily and are primarily driven by supply, demand, and energy prices.

However, as a rule of thumb, stainless steels cost four to five times much as carbon steel in terms of material costs. Carbon steel is about $500/ton, while stainless steel costs about $2000/ton. The more alloying elements the steel contains, the more expensive it is. Based on that rule, it is logical to assume that the 316L austenitic stainless steel and the 13% Cr martensitic stainless steel will cost less than the 22% Cr and the 25% Cr duplex stainless steel. The nickel-based steels would probably cost around the price of the duplex stainless steels. Numerous kinds of steel, from low to high carbon, and a wide range of evaluations of stainless steel change immensely in expense. For example, Inconel 600 (registered trademark of Special Metals), which is one of a family of austenitic nickel-chromium-based superalloys, costs about $40000/ton.