The electron’s antiparticle is called the positron; it is identical to the electron, except it carries electrical and other charges of the opposite sign. When an electron collides with a positron, both particles can be totally annihilated, producing gamma-ray photons.

The electron’s antiparticle is called the positron; it is identical to the electron, except it carries electrical and other charges of the opposite sign. When an electron collides with a positron, both particles can be totally annihilated, producing gamma-ray photons.

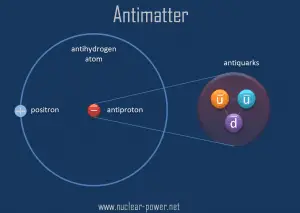

The positrons are positively charged (+1e), almost massless particles. Their rest mass equals 9.109 × 10−31 kg (510.998 keV/c2) (approximately 1/1836 that of the proton).

Like all elementary particles, electrons exhibit properties of both particles and waves: they can collide with other particles and can be diffracted like light. The original idea for antiparticles came from a relativistic wave equation developed in 1928 by the English scientist P. A. M. Dirac (1902-1984). He realized that his relativistic version of the Schrödinger wave equation for electrons predicted the possibility of antielectrons. Paul Dirac and Carl D. Anderson discovered these in 1932 and named them positrons. They studied cosmic-ray collisions via a cloud chamber – a particle detector in which moving electrons (or positrons) leave behind trails as they move through the gas. Positron paths in a cloud chamber trace the same helical path as an electron but rotate in the opposite direction for the magnetic field direction. They have the same magnitude of charge-to-mass ratio but with opposite charges and, therefore, opposite signed charge-to-mass ratios. Although Dirac did not himself use the term antimatter, its use follows naturally enough from antielectrons, antiprotons, etc.

See also: Positron Interaction

See also: Shielding of Positrons