the change in energy (in kJ/mole) of a neutral atom or molecule (in the gaseous phase) when an electron is added to the atom to form a negative ion.

X + e– → X– + energy Affinity = – ∆H

In other words, it can be expressed as the neutral atom’s likelihood of gaining an electron. Note that ionization energies measure the tendency of a neutral atom to resist the loss of electrons. Electron affinities are more difficult to measure than ionization energies.

A fluorine atom in the gas phase, for example, gives off energy when it gains an electron to form a fluoride ion.

F + e– → F– – ∆H = Affinity = 328 kJ/mol

Electron affinity is one of the most important parameters that guide chemical reactivity. Molecules with high electron affinity form very stable negative ions, important in the chemical and health industry. They purify the air, lift mood, and, most importantly, act as strong oxidizing agents. It is essential to keep track of signs to use electron affinities properly. When an electron is added to a neutral atom, energy is released. This affinity is known as the first electron affinity, and these energies are negative. By convention, the negative sign shows a release of energy. However, more energy is required to add an electron to a negative ion which overwhelms any release of energy from the electron attachment process. This affinity is known as the second electron affinity, and these energies are positive.

Halogens have the highest electron affinities among all elements, and the electron affinity of Cl, 3.62 eV, is the largest of all the elements. Superhalogens are molecules that have electron affinities (EA) greater than that of Cl, the element with the highest EA (3.62 eV).

It is well known that noble gases have closed electronic shell structures and hence have high ionization potentials and low electron affinities. They are chemically inert and resistant to salt formation under most conditions.

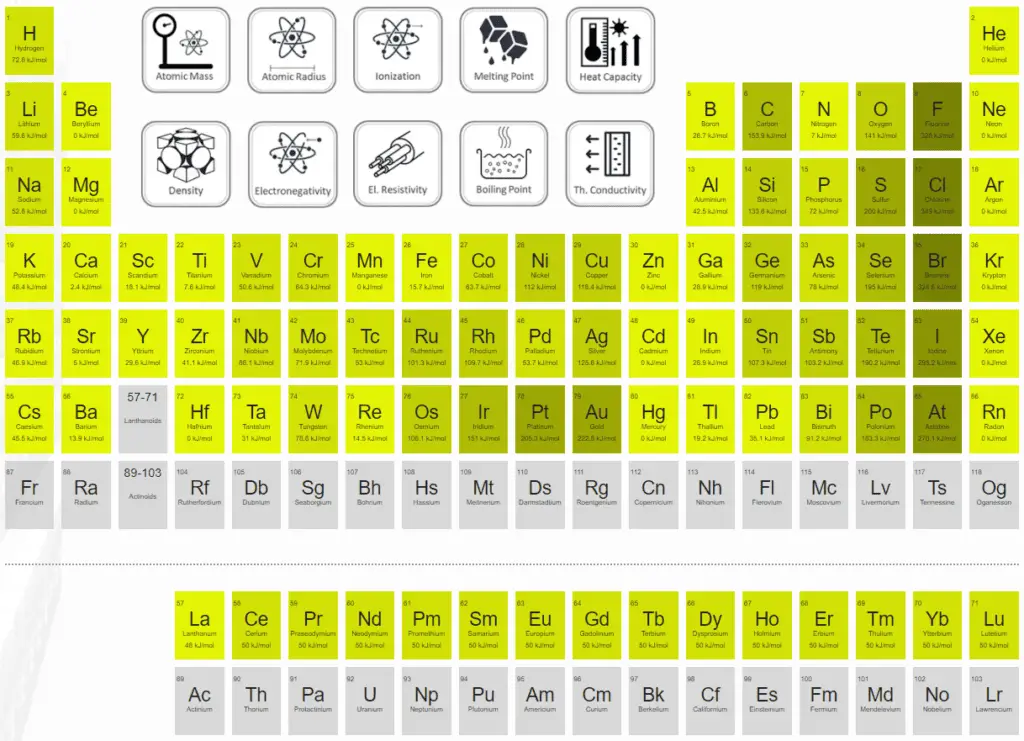

Electron affinity in the periodic table

For full interactivity, please visit material-properties.org.

Affinities of Nonmetals vs. Affinities of Metals

- Metals: Metals like to lose valence electrons to form cations to have a fully stable shell. The electron affinity of metals is lower than that of nonmetals, and mercury most weakly attracts an extra electron.

- Nonmetals: Generally, nonmetals have more positive electron affinity than metals. Nonmetals like to gain electrons to form anions with a fully stable electron shell, and chlorine most strongly attracts extra electrons. The electron affinities of the noble gases have not been conclusively measured, so they may or may not have slightly negative values.