X-rays, also known as X-radiation, refer to electromagnetic radiation (no rest mass, no charge) of high energies. X-rays are high-energy photons with short wavelengths and thus very high frequency. The radiation frequency is the key parameter of all photons because it determines the energy of a photon. Photons are categorized according to their energies, from low-energy radio waves and infrared radiation, through visible light, to high-energy X-rays and gamma rays.

Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 0.01 to 10 nanometers (3×1016 Hz to 3×1019 Hz), corresponding to energies in the range of 100 eV to 100 keV. X-ray wavelengths are shorter than those of UV rays and typically longer than those of gamma rays. The distinction between X-rays and gamma rays is not so simple and has changed in recent decades. According to the currently valid definition, X-rays are emitted by electrons outside the nucleus, while gamma rays are emitted by the nucleus.

Since the X-rays (especially hard X-rays) are in substance high-energy photons, they are very penetrating matter and are thus biologically hazardous. X-rays can travel thousands of feet in the air and easily pass through the human body.

Interaction of X-rays with Matter

Although many possible interactions are known, there are three key interaction mechanisms with the matter. The strength of these interactions depends on the energy of the X-rays and the elemental composition of the material. Still, not much on chemical properties, since the X-ray photon energy is much higher than chemical binding energies. The photoelectric absorption dominates at low-energies of X-rays, while Compton scattering dominates at higher energies.

- Photoelectric absorption

- Compton scattering

- Rayleigh scattering

Photoelectric Absorption of X-rays

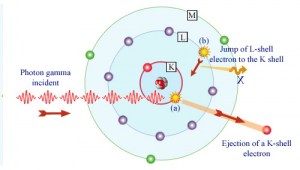

In the photoelectric effect, a photon undergoes an interaction with an electron that is bound in an atom. In this interaction, the incident photon completely disappears, and an energetic photoelectron is ejected by the atom from one of its bound shells. The kinetic energy of the ejected photoelectron (Ee) is equal to the incident photon energy (hν) minus the binding energy of the photoelectron in its original shell (Eb).

Ee=hν-Eb

Therefore photoelectrons are only emitted by the photoelectric effect if a photon reaches or exceeds threshold energy – the binding energy of the electron – the work function of the material. For very high X-rays with energies of more than hundreds of keV, the photoelectron carries off the majority of the incident photon energy – hν.

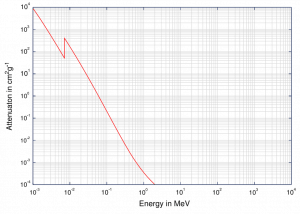

At small values of gamma-ray energy, the photoelectric effect dominates. The mechanism is also enhanced for materials of high atomic number Z. It is not simple to derive an analytic expression for the probability of photoelectric absorption of gamma-ray per atom over all ranges of gamma-ray energies. The probability of photoelectric absorption per unit mass is approximately proportional to:

τ(photoelectric) = constant x ZN/E3.5

where Z is the atomic number, and the exponent n varies between 4 and 5. E is the energy of the incident photon. The proportionality to higher powers of the atomic number Z is the main reason for using high Z materials, such as lead or depleted uranium in gamma-ray shields.

Although the probability of the photoelectric absorption of a photon decreases, in general, with increasing photon energy, there are sharp discontinuities in the cross-section curve. These are called “absorption edges,” and they correspond to the binding energies of electrons from an atom’s bound shells. For photons with the energy just above the edge, the photon energy is sufficient to undergo the photoelectric interaction with the electron from a bound shell, let’s say K-shell. The probability of such interaction is just above this edge, much greater than that of photons of energy slightly below this edge. For photons below this edge, the interaction with an electron from K-shell is energetically impossible; therefore, the probability drops abruptly. These edges also occur at binding energies of electrons from other shells (L, M, N …).

Although the probability of the photoelectric absorption of a photon decreases, in general, with increasing photon energy, there are sharp discontinuities in the cross-section curve. These are called “absorption edges,” and they correspond to the binding energies of electrons from an atom’s bound shells. For photons with the energy just above the edge, the photon energy is sufficient to undergo the photoelectric interaction with the electron from a bound shell, let’s say K-shell. The probability of such interaction is just above this edge, much greater than that of photons of energy slightly below this edge. For photons below this edge, the interaction with an electron from K-shell is energetically impossible; therefore, the probability drops abruptly. These edges also occur at binding energies of electrons from other shells (L, M, N …).

Compton Scattering of X-rays

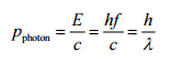

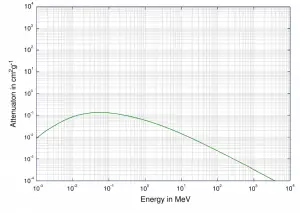

The Compton formula was published in 1923 in the Physical Review. Compton explained that the X-ray shift is caused by the particle-like momentum of photons. Compton scattering formula is the mathematical relationship between the shift in wavelength and the scattering angle of the X-rays. In the case of Compton scattering, the photon of frequency f collides with an electron at rest. Upon collision, the photon bounces off the electron, giving up some of its initial energy (given by Planck’s formula E=hf). While the electron gains momentum (mass x velocity), the photon cannot lower its velocity. As a result of momentum conservation law, the photon must lower its momentum given by:

The Compton formula was published in 1923 in the Physical Review. Compton explained that the X-ray shift is caused by the particle-like momentum of photons. Compton scattering formula is the mathematical relationship between the shift in wavelength and the scattering angle of the X-rays. In the case of Compton scattering, the photon of frequency f collides with an electron at rest. Upon collision, the photon bounces off the electron, giving up some of its initial energy (given by Planck’s formula E=hf). While the electron gains momentum (mass x velocity), the photon cannot lower its velocity. As a result of momentum conservation law, the photon must lower its momentum given by:

Source: hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu

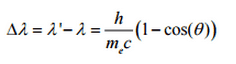

So the decrease in photon’s momentum must be translated into a decrease in frequency (increase in wavelength Δλ = λ’ – λ). The shift of the wavelength increased with scattering angle according to the Compton formula:

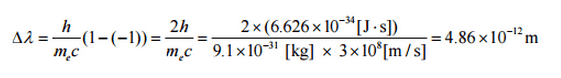

where λ is the initial wavelength of the photon, λ’ is the wavelength after scattering, h is the Planck constant = 6.626 x 10-34 J.s, and me is the electron rest mass (0.511 MeV), c is the speed of light, Θ is the scattering angle. The minimum change in wavelength (λ′ − λ) for the photon occurs when Θ = 0° (cos(Θ)=1) and is at least zero. The maximum change in wavelength (λ′ − λ) for the photon occurs when Θ = 180° (cos(Θ)=-1). In this case, the photon transfers to the electron as much momentum as possible. The maximum change in wavelength can be derived from the Compton formula:

The quantity h/mec is known as the Compton wavelength of the electron and is equal to 2.43×10−12 m.

Rayleigh Scattering – Thomson Scattering

Rayleigh scattering, also known as Thomson scattering, is the low-energy limit of Compton scattering. The particle kinetic energy and photon frequency do not change due to the scattering. Rayleigh scattering occurs due to an interaction between an incoming photon and an electron, the binding energy of which is significantly greater than that of the incoming photon. The incident radiation is assumed to set the electron into forced resonant oscillation such that the electron re-emits radiation of the same frequency but in all directions. In this case, the electric field of the incident wave (photon) accelerates the charged particle, causing it, in turn, to emit radiation at the same frequency as the incident wave, and thus the wave is scattered. Rayleigh scattering is significant up to ≈ 20keV and elastic like Thomson scattering. The total scattering cross-section combines the Rayleigh and Compton bound scattering cross-sections. Thomson scattering is an important phenomenon in plasma physics and was first explained by the physicist J. J. Thomson. This interaction has great significance in the area of X-ray crystallography.