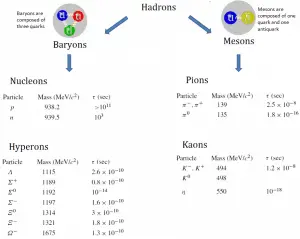

Protons and neutrons each contain three quarks; they belong to the family of particles called the baryons. Other baryons are the lambda, sigma, xi, and omega particles. On the other hand, mesons bosons and are composed of two quarks: a quark and an antiquark. Besides charge and spin (1/2 for the baryons), two other quantum numbers are assigned to these particles: baryon number (B) and strangeness (S). Baryons have a baryon number, B, of 1, while their antiparticles, called antibaryons, have a baryon number of −1. A nucleus of deuterium (deuteron), for example, contains one proton and one neutron (each with a baryon number of 1) and has a baryon number of 2.

Since baryons make up most of the mass of ordinary atoms, everyday matter is often referred to as baryonic matter.

Since baryons make up most of the mass of ordinary atoms, everyday matter is often referred to as baryonic matter.

The conservation of baryon number is an important rule for interactions and decays of baryons. No known interactions violate the conservation of the baryon number.

Baryon Number

In particle physics, the baryon number denotes which particles are baryons and which particles are not. Each baryon has a baryon number of 1, and each antibaryon has a baryon number of -1. Other non-baryonic particles have a baryon number of 0. Since there are exotic hadrons like pentaquarks and tetraquarks, there is a general definition of baryon number as:

where nq is the number of quarks, and nq is the number of antiquarks.

The baryon number is a conserved quantum number in all particle reactions. The term conserved means that the sum of the baryon number of all incoming particles is the same as the sum of the baryon numbers of all particles resulting from the reaction. A slight asymmetry in the laws of physics allowed baryons to be created in the Big Bang.

Law of Conservation of Baryon Number

In analyzing nuclear reactions, we apply the many conservation laws. Nuclear reactions are subject to classical conservation laws for momentum, angular momentum, and energy (including rest energies). Additional conservation laws not anticipated by classical physics are electric charge, lepton number, and baryon number. Certain of these laws are obeyed under all circumstances, and others are not.

Baryon number is a generalization of nucleon number, which is conserved in non-relativistic nuclear reactions and decays. The law of conservation of baryon number states that:

The sum of the baryon number of all incoming particles is the same as the sum of the baryon numbers of all particles resulting from the reaction.

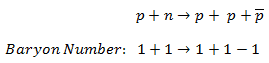

For example, the following reaction has never been observed:

even if the incoming photon has sufficient energy and charge, energy, and so on, are conserved. This reaction does not conserve the baryon number since the left side has B =+2, and the right has B =+1.

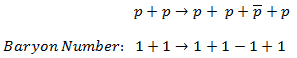

On the other hand, the following reaction (proton-antiproton pair production) does conserve B and does occur if the incoming proton has sufficient energy (the threshold energy = 5.6 GeV):

As indicated, B = +2 on both sides of this equation.

From these and other reactions, the conservation of the baryon number has been established as a basic principle of physics.

This principle provides the basis for the stability of the proton. Since the proton is the lightest particle among all baryons, the hypothetical products of its decay would have to be non-baryons. Thus, the decay would violate the conservation of the baryon number. It must be added some theories have suggested that protons are, in fact, unstable with a very long half-life (~1030 years) and that they decay into leptons. There is currently no experimental evidence that proton decay occurs.