In general, semiconductors are inorganic or organic materials that can control their conduction depending on chemical structure, temperature, illumination, and the presence of dopants. The name semiconductor comes from the fact that these materials have electrical conductivity between a metal, like copper, gold, etc., and an insulator, like glass. They have an energy gap of less than 4eV (about 1eV). In solid-state physics, this energy gap or band gap is an energy range between the valence band and conduction band where electron states are forbidden. In contrast to conductors, semiconductors’ electrons must obtain energy (e.g., from ionizing radiation) to cross the band gap and reach the conduction band. Properties of semiconductors are determined by the energy gap between valence and conduction bands.

Types of Semiconductors

Semiconductor Materials

There are many types of semiconductors in nature and others synthesized in laboratories; however, the best known are silicon (Si) and germanium (Ge).

Types of semiconductors:

-

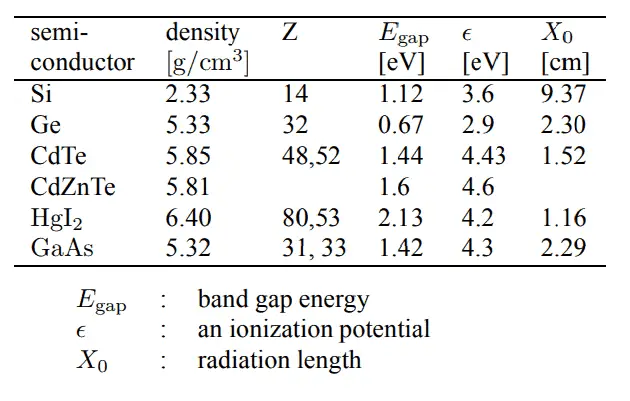

Purified silicon. Source: wikipedia.org License: Public Domain Silicon. Silicon is a chemical element with the atomic number 14, meaning there are 14 protons and 14 electrons in the atomic structure. The chemical symbol for Silicon is Si. Silicon is a hard and brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and it is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. Silicon is mainly used for charged particle detectors (especially for tracking charged particles) and soft X-ray detectors. The large band-gap energy (Egap= 1.12 eV) allows us to operate the detector at room temperature, but cooling is preferred to reduce noise. Silicon-based detectors are very important in high-energy physics. Since silicon-based detectors are very good for tracking charged particles, they constitute a substantial part of the detection system at the LHC in CERN.

-

12 grams polycrystalline germanium. Source: wikipedia.org License: CC BY 3.0 Germanium. Germanium is a chemical element with the atomic number 32, which means there are 32 protons and 32 electrons in the atomic structure. The chemical symbol for Germanium is Ge. Germanium is a lustrous, hard, grayish-white metalloid in the carbon group, chemically similar to its group neighbors, tin and silicon. Pure germanium is a semiconductor with an appearance similar to elemental silicon. Germanium is widely used for gamma-ray spectroscopy. In gamma spectroscopy, germanium is preferred due to its atomic number being much higher than silicon, increasing the probability of gamma-ray interaction. Germanium is more used than silicon for radiation detection because the average energy necessary to create an electron-hole pair is 3.6 eV for silicon and 2.9 eV for germanium, which provides the latter a better resolution in energy. On the other hand, germanium has a small band gap energy (Egap = 0.67 eV), which requires operating the detector at cryogenic temperatures.

- Diamond. Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamonds are also very good electrical insulators, which are both useful and problematic for electrical devices. Diamond is a wide-bandgap semiconductor (Egap= 5.47 eV) with high potential as an electronic device material in many devices. Diamond detectors have many similarities with silicon detectors but are expected to offer significant advantages, particularly high radiation hardness and very low drift currents.

CdTe and CdZnTe. Cadmium telluride (CdTe) and cadmium zinc telluride (CdZnTe) are promising semiconductor materials for hard X-ray and gamma-ray detection. These materials’ high atomic number and density mean they can effectively attenuate X-rays and gamma rays with energies greater than 20 keV that traditional silicon-based sensors cannot detect. This significantly increases their quantum efficiency in comparison with silicon-based. The large band-gap energy (Egap= 1.44 eV) allows us to operate the detector at room temperature. On the other hand, a considerable amount of charge loss in these detectors produces a reduced energy resolution.

CdTe and CdZnTe. Cadmium telluride (CdTe) and cadmium zinc telluride (CdZnTe) are promising semiconductor materials for hard X-ray and gamma-ray detection. These materials’ high atomic number and density mean they can effectively attenuate X-rays and gamma rays with energies greater than 20 keV that traditional silicon-based sensors cannot detect. This significantly increases their quantum efficiency in comparison with silicon-based. The large band-gap energy (Egap= 1.44 eV) allows us to operate the detector at room temperature. On the other hand, a considerable amount of charge loss in these detectors produces a reduced energy resolution.

Intrinsic Semiconductor – Pure Semiconductor

An intrinsic semiconductor is completely pure without any significant dopant species. Therefore, intrinsic semiconductors are also known as pure semiconductors or i-type semiconductors.

![]() The number of charge carriers at a certain temperature is therefore determined by the material’s properties instead of the number of impurities. Note that a 1 cm3 sample of pure germanium at 20 °C contains about 4.2×1022 atoms but also contains about 2.5 x 1013 free electrons and 2.5 x 1013 holes. These charge carriers are produced by thermal excitation. In intrinsic semiconductors, the number of excited electrons and the number of holes are equal: n = p. Electrons and holes are created by the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band. An electron-hole (often simply called a hole) is the lack of an electron at a position where one could exist in an atom or atomic lattice. This equality may even be the case after doping the semiconductor, though only if it is doped with both donors and acceptors equally. In this case, n = p still holds, and the semiconductor remains intrinsic, though doped.

The number of charge carriers at a certain temperature is therefore determined by the material’s properties instead of the number of impurities. Note that a 1 cm3 sample of pure germanium at 20 °C contains about 4.2×1022 atoms but also contains about 2.5 x 1013 free electrons and 2.5 x 1013 holes. These charge carriers are produced by thermal excitation. In intrinsic semiconductors, the number of excited electrons and the number of holes are equal: n = p. Electrons and holes are created by the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band. An electron-hole (often simply called a hole) is the lack of an electron at a position where one could exist in an atom or atomic lattice. This equality may even be the case after doping the semiconductor, though only if it is doped with both donors and acceptors equally. In this case, n = p still holds, and the semiconductor remains intrinsic, though doped.

Semiconductors have an energy gap of less than 4eV (about 1eV). Band gaps are naturally different for different materials. For example, diamond is a wide-bandgap semiconductor (Egap= 5.47 eV) with high potential as an electronic device material in many devices. On the other side, germanium has a small band gap energy (Egap = 0.67 eV), which requires operating the detector at cryogenic temperatures. In solid-state physics, this energy gap or band gap is an energy range between the valence band and conduction band where electron states are forbidden. In contrast to conductors, semiconductors’ electrons must obtain energy (e.g., from ionizing radiation) to cross the band gap and reach the conduction band.

Intrinsic semiconductors, however, are not very useful, as they are neither very good insulators nor very good conductors. However, one important feature of semiconductors is that their conductivity can be increased and controlled by doping with impurities and gating with electric fields. Recall that a 1 cm3 sample of pure germanium at 20 °C contains about 4.2×1022 atoms but also contains about 2.5 x 1013 free electrons and 2.5 x 1013 holes constantly generated from thermal energy. Total absorption of a 1 MeV photon produces around 3 x 105 electron-hole pairs. This value is minor compared to the total number of free carriers in a 1 cm3 intrinsic semiconductor. As can be seen, the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) would be minimal. Adding 0.001% of arsenic (an impurity) donates an extra 1017 free electrons in the same volume, and the electrical conductivity is increased by a factor of 10,000. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) would be even smaller in doped material. Because germanium has a relatively low band gap, these detectors must be cooled to reduce the thermal generation of charge carriers to an acceptable level. Otherwise, leakage current-induced noise destroys the energy resolution of the detector. Doping and gating move the conduction or valence band much closer to the Fermi level and greatly increase the number of partially filled states.

Extrinsic Semiconductors – Doped Semiconductors

An extrinsic semiconductor, or doped semiconductor, is a semiconductor that was intentionally doped to modulate its electrical, optical, and structural properties. In the case of semiconductor detectors of ionizing radiation, doping is the intentional introduction of impurities into an intrinsic semiconductor for the purpose of changes in their electrical properties. Therefore, intrinsic semiconductors are also known as pure semiconductors or i-type semiconductors.

The addition of a small percentage of foreign atoms in the regular crystal lattice of silicon or germanium produces dramatic changes in their electrical properties since these foreign atoms incorporated into the crystal structure of the semiconductor provide free charge carriers (electrons or electron holes) in the semiconductor. In an extrinsic semiconductor, these foreign dopant atoms in the crystal lattice mainly provide the charge carriers that carry electric current through the crystal. Two types of dopant atoms generally result in two types of extrinsic semiconductors. These dopants that produce the desired controlled changes are classified as either electron acceptors or donors, and the corresponding doped semiconductors are known as:

- n-type Semiconductors.

- p-type Semiconductors.

Extrinsic semiconductors are components of many common electrical devices, as well as many detectors of ionizing radiation. For these purposes, a semiconductor diode (devices that allow current in only one direction) usually consists of p-type and n-type semiconductors placed in a junction with one another.

n-type Semiconductors

![]() An extrinsic semiconductor doped with electron donor atoms is called an n-type semiconductor because most charge carriers in the crystal are negative electrons. Since silicon is a tetravalent element, the normal crystal structure contains 4 covalent bonds from four valence electrons. The most common dopants in silicon are group III and V elements. Group V elements (pentavalent) have five valence electrons, allowing them to act as donors. That means adding these pentavalent impurities such as arsenic, antimony, or phosphorus contributes to free electrons, greatly increasing the conductivity of the intrinsic semiconductor. For example, a silicon crystal doped with boron (group III) creates a p-type semiconductor, whereas a crystal doped with phosphorus (group V) results in an n-type semiconductor.

An extrinsic semiconductor doped with electron donor atoms is called an n-type semiconductor because most charge carriers in the crystal are negative electrons. Since silicon is a tetravalent element, the normal crystal structure contains 4 covalent bonds from four valence electrons. The most common dopants in silicon are group III and V elements. Group V elements (pentavalent) have five valence electrons, allowing them to act as donors. That means adding these pentavalent impurities such as arsenic, antimony, or phosphorus contributes to free electrons, greatly increasing the conductivity of the intrinsic semiconductor. For example, a silicon crystal doped with boron (group III) creates a p-type semiconductor, whereas a crystal doped with phosphorus (group V) results in an n-type semiconductor.

The conduction electrons are completely dominated by the number of donor electrons. Therefore:

The total number of conduction electrons is approximately equal to the number of donor sites, n≈ND.

The charge neutrality of semiconductor material is maintained because excited donor sites balance the conduction electrons. The net result is that the number of conduction electrons increases while the number of holes is reduced. The imbalance of the carrier concentration in the respective bands is expressed by the different absolute number of electrons and holes. Electrons are majority carriers, while holes are minority carriers in n-type material.

p-type Semiconductors

![]() An extrinsic semiconductor doped with electron acceptor atoms is called a p-type semiconductor because most charge carriers in the crystal are electron holes (positive charge carriers). The pure semiconductor silicon is a tetravalent element, and the normal crystal structure contains 4 covalent bonds from four valence electrons. In silicon, the most common dopants are group III and group V elements. Group III elements (trivalent) all contain three valence electrons, causing them to function as acceptors when used to dope silicon. When an acceptor atom replaces a tetravalent silicon atom in the crystal, a vacant state (an electron-hole) is created. An electron-hole (often simply called a hole) is the lack of an electron at a position where one could exist in an atom or atomic lattice. It is one of the two charge carriers responsible for creating an electric current in semiconducting materials. These positively charged holes can move from atom to atom in semiconducting materials as electrons leave their positions. Adding trivalent impurities such as boron, aluminum, or gallium to an intrinsic semiconductor creates these positive electron holes in the structure. For example, a silicon crystal doped with boron (group III) creates a p-type semiconductor, whereas a crystal doped with phosphorus (group V) results in an n-type semiconductor.

An extrinsic semiconductor doped with electron acceptor atoms is called a p-type semiconductor because most charge carriers in the crystal are electron holes (positive charge carriers). The pure semiconductor silicon is a tetravalent element, and the normal crystal structure contains 4 covalent bonds from four valence electrons. In silicon, the most common dopants are group III and group V elements. Group III elements (trivalent) all contain three valence electrons, causing them to function as acceptors when used to dope silicon. When an acceptor atom replaces a tetravalent silicon atom in the crystal, a vacant state (an electron-hole) is created. An electron-hole (often simply called a hole) is the lack of an electron at a position where one could exist in an atom or atomic lattice. It is one of the two charge carriers responsible for creating an electric current in semiconducting materials. These positively charged holes can move from atom to atom in semiconducting materials as electrons leave their positions. Adding trivalent impurities such as boron, aluminum, or gallium to an intrinsic semiconductor creates these positive electron holes in the structure. For example, a silicon crystal doped with boron (group III) creates a p-type semiconductor, whereas a crystal doped with phosphorus (group V) results in an n-type semiconductor.

The number of acceptor sites completely dominates the number of electron holes. Therefore:

The total number of holes is approximately equal to the number of donor sites, p ≈ NA.

The charge neutrality of this semiconductor material is also maintained. The net result is that the number of electron holes is increased while the number of conduction electrons is reduced. The imbalance of the carrier concentration in the respective bands is expressed by the different absolute number of electrons and holes. Electron holes are majority carriers, while electrons are minority carriers in p-type material.

The P-N Junction – Reverse Biased Junction

The semiconductor detector operates much better as a radiation detector if an external voltage is applied across the junction in the reverse-biased direction. The depletion region will function as a radiation detector. Improvement can be achieved by using a reverse-bias voltage to the P-N junction to deplete the detector of free carriers, which is the principle of most semiconductor detectors. Reverse biasing a junction increases the thickness of the depletion region because the potential difference across the junction is enhanced. Germanium detectors have a p-i-n structure in which the intrinsic (i) region is sensitive to ionizing radiation, particularly X and gamma rays. Under reverse bias, an electric field extends across the intrinsic or depleted region. In this case, a negative voltage is applied to the p-side and positive to the second one. Holes in the p-region are attracted from the junction towards the p contact and similarly for electrons and the n contact. In proportion to the energy deposited in the detector by the incoming photon, this charge is converted into a voltage pulse by an integral charge-sensitive preamplifier.

See also: Germanium Detectors, MIRION Technologies. <available from: https://www.mirion.com/products/germanium-detectors>.