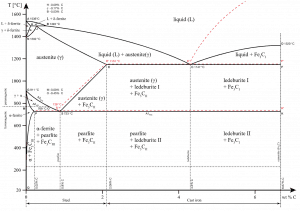

In materials engineering, cast irons are a class of ferrous alloys with carbon contents above 2.14 wt%. Typically, cast irons contain from 2.14 wt% to 4.0 wt% carbon and anywhere from 0.5 wt% to 3 wt% of silicon. Iron alloys with lower carbon content are known as steel. The difference is that cast irons can take advantage of eutectic solidification in the binary iron-carbon system. Eutectic is Greek for “easy or well melting.” The eutectic point represents the composition on the phase diagram where the lowest melting temperature is achieved. For the iron-carbon system, the eutectic point occurs at a composition of 4.26 wt% C and a temperature of 1148°C.

See also: Types of Cast Irons

Malleable Cast Iron

Malleable cast iron is white cast iron that has been annealed. An annealing heat treatment transforms the brittle structure as the first cast into the malleable form. Therefore, its composition is similar to white cast iron, with slightly higher amounts of carbon and silicon. Malleable iron contains graphite nodules that are not truly spherical as they are in ductile iron because they are formed from heat treatment rather than during cooling from the melt. Malleable iron is made by first casting a white iron so that flakes of graphite are avoided, and all the undissolved carbon is in the form of iron carbide. Malleable iron starts as a white iron casting that is heat treated for a day or two at about 950 °C (1,740 °F) and then cools over a day or two. As a result, the carbon in iron carbide transforms into graphite nodules surrounded by a ferrite or pearlite matrix, depending on the cooling rate. The slow process allows the surface tension to form the graphite nodules rather than flakes. Malleable iron, like ductile iron, possesses considerable ductility and toughness because it combines nodular graphite and low carbon metallic matrix. Like ductile iron, malleable iron also exhibits high resistance to corrosion and excellent machinability. Malleable iron’s good damping capacity and fatigue strength are also useful for long service in highly stressed parts. There are two types of ferritic malleable iron: blackheart and whiteheart.

It is often used for small castings requiring good tensile strength and the ability to flex without breaking (ductility). Applications of malleable cast irons include many essential automotive parts such as differential carriers, differential cases, bearing caps, and steering-gear housings. Other uses include hand tools, brackets, machine parts, electrical fittings, pipe fittings, farm equipment, and mining hardware.

Properties of Malleable Cast Iron – ASTM A220

Material properties are intensive properties, which means they are independent of the amount of mass and may vary from place to place within the system at any moment. Materials science involves studying materials’ structure and relating them to their properties (mechanical, electrical, etc.). Once materials scientist knows about this structure-property correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a material in a given application. The major determinants of the structure of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical elements and how it has been processed into its final form.

Mechanical Properties of Malleable Cast Iron – ASTM A220

Materials are frequently chosen for various applications because they have desirable combinations of mechanical characteristics. For structural applications, material properties are crucial, and engineers must consider them.

Strength of Malleable Cast Iron – ASTM A220

In the mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. The strength of materials considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. The strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

The ultimate tensile strength of malleable cast iron – ASTM A220 is 580 MPa.

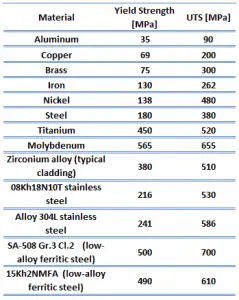

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

Yield Strength

The yield strength of malleable cast iron – ASTM A220 is 480 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically. In contrast, the yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Before the yield point, the material will deform elastically and return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behavior termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for high-strength steel.

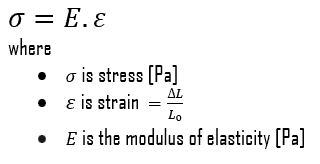

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

Young’s modulus of elasticity of malleable cast iron – ASTM A220 is 172 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on the removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position, and all the atoms are displaced the same amount and maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions, and no permanent deformation occurs. According to Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.

The hardness of Malleable Cast Iron – ASTM A220

Brinell hardness of malleable cast iron – ASTM A220 is approximately 250 MPa.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, abrasion, indentation, or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, abrasion, indentation, or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

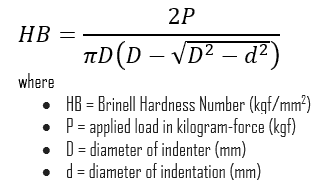

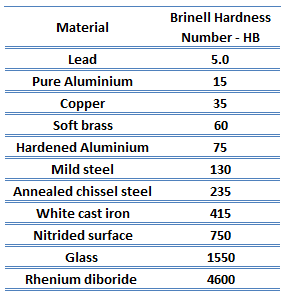

Brinell hardness test is one of the indentation hardness tests developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from Brinell, and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards, HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are various test methods in common use (e.g., Brinell, Knoop, Vickers, and Rockwell). Some tables correlate the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

Thermal Properties of Malleable Cast Iron – ASTM A220

Thermal properties of materials refer to the response of materials to changes in their temperature and the application of heat. As a solid absorbs energy in the form of heat, its temperature rises, and its dimensions increase. But different materials react to the application of heat differently.

Heat capacity, thermal expansion, and thermal conductivity are often critical in solids’ practical use.

Melting Point of Malleable Cast Iron – ASTM A220

The melting point of malleable cast iron – ASTM A220 is around 1260°C.

In general, melting is a phase change of a substance from the solid to the liquid phase. The melting point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change occurs. The melting point also defines a condition where the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium.

Thermal Conductivity of Malleable Cast Iron – ASTM A220

The thermal conductivity of malleable cast iron is approximately 40 W/(m. K).

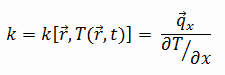

The heat transfer characteristics of solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It measures a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies to all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas). Therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature, and for vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are nearly homogeneous. Therefore we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material, the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k.