An alloy is a mixture of two or more materials, at least one of which is a metal. Alloys can have a microstructure consisting of solid solutions, where secondary atoms are introduced as substitutionals or interstitials in a crystal lattice. An alloy may also be a mixture of metallic phases (two or more solutions, forming a microstructure of different crystals within the metal).

But all alloys can exist in different phases. Phases are physically homogeneous states of an alloy. A phase has a precise chemical composition – a certain arrangement and bonding between the atoms, and this structure of atoms imparts different properties to different phases. Phase diagrams are graphical representations of the phases present in an alloy at different conditions of temperature, pressure, or chemical composition.

Phase Diagram of Iron-carbon System

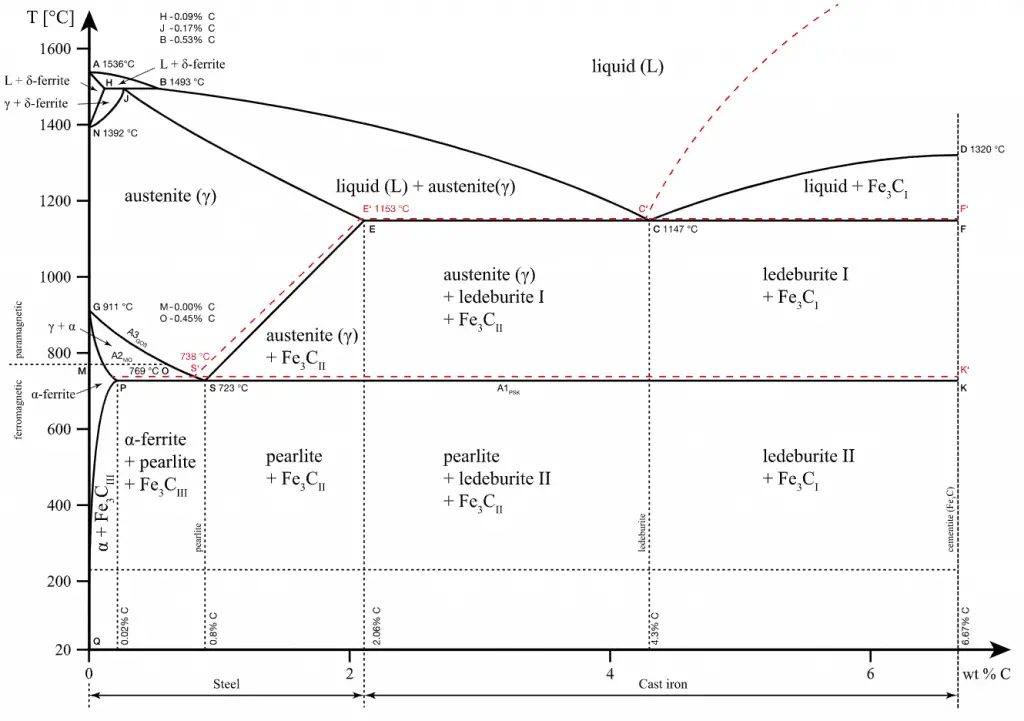

The simplest ferrous alloys are known as steels, and they consist of iron (Fe) alloyed with carbon (C) (about 0.1% to 1%, depending on the type). Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for greater strength. Due to its very-high strength, but still substantial toughness, and its ability to be greatly altered by heat treatment, steel is one of the most useful and common ferrous alloys in modern use. The figure shows the iron–iron carbide (Fe–Fe3C) phase diagram. The percentage of carbon present and the temperature define the iron carbon alloy’s phase ande, its physical characteristics and mechanical properties. The percentage of carbon determines the type of ferrous alloy: iron, steel, or cast iron.

Common Phases in Steels and Irons

Heat treatment of steels requires an understanding of both the equilibrium phases and the metastable phases that occur during heating and/or cooling. For steels, the stable equilibrium phases include:

- Ferrite. Ferrite or α-ferrite is a body-centered cubic structure phase of iron that exists below temperatures of 912°C for low concentrations of carbon in iron. α-ferrite can only dissolve up to 0.02 percent of carbon at 727°C. This is because of the configuration of the iron lattice, which forms a BCC crystal structure. The primary phase of low-carbon or mild steel and most cast irons at room temperature is ferromagnetic α-Fe.

- Austenite. Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a non-magnetic face-centered cubic structure phase of iron. Austenite in iron-carbon alloys is generally only present above the critical eutectoid temperature (723°C) and below 1500°C, depending on carbon content. However, it can be retained to room temperature by alloy additions such as nickel or manganese. Carbon plays an important role in heat treatment because it expands the temperature range of austenite stability. Higher carbon content lowers the temperature needed to austenitize steel—such that iron atoms rearrange themselves to form an fcc lattice structure. Austenite is present in the most commonly used type of stainless steel, which is very well known for its corrosion resistance.

- Graphite. Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for greater strength.

- Cementite. Cementite (Fe3C) is a metastable compound, and under some circumstances, it can be made to dissociate or decompose to form α-ferrite and graphite, according to the reaction: Fe3C → 3Fe (α) + C (graphite). Cementite in its pure form is ceramic, and is hard and brittle,, making it suitable for strengthening steels. Its mechanical properties are a function of its microstructure, which depends upon how it is mixed with ferrite.

The metastable phases are:

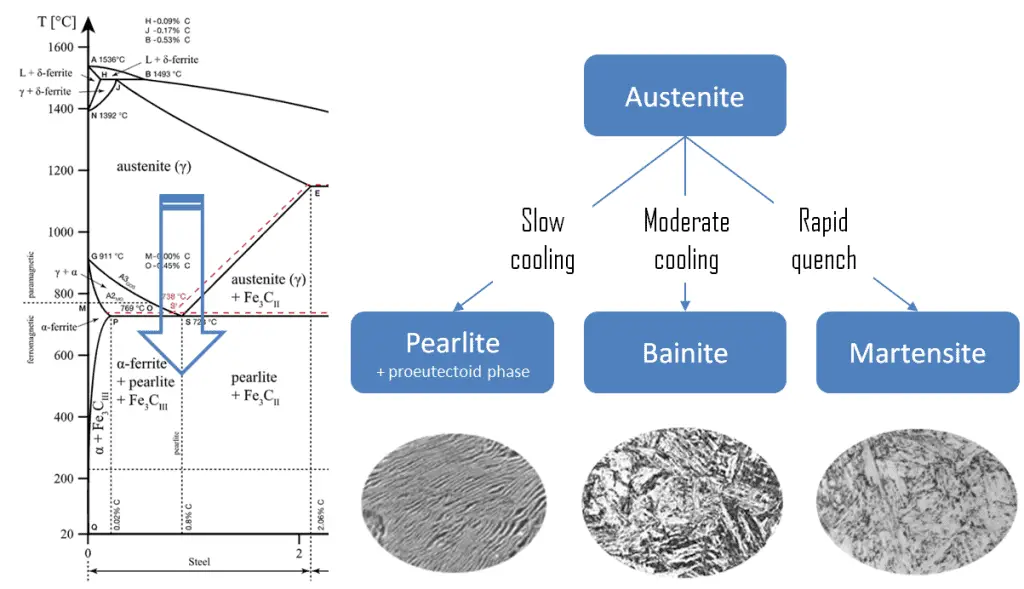

Pearlite. In metallurgy, pearlite is a layered metallic structure of two phases, composed of alternating ferrite layers (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. It is named for its resemblance to the mother of the pearl.

Pearlite. In metallurgy, pearlite is a layered metallic structure of two phases, composed of alternating ferrite layers (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. It is named for its resemblance to the mother of the pearl.- Martensite. Martensite is a very hard metastable structure with a body-centered tetragonal (BCT) crystal structure. Martensite is formed in steels when austenite’s cooling rate is so high that carbon atoms do not have time to diffuse out of the crystal structure in large enough quantities to form cementite (Fe3C).

- Bainite. Bainite is a plate-like microstructure that forms in steels from austenite when cooling rates are not rapid

enough to produce martensite but are still fast enough so that carbon does not have enough time to diffuse to form pearlite. Bainitic steels are generally stronger and harder than pearlitic steels, yet they exhibit a desirable combination of strength and ductility.

Critical Temperature of Steel

The critical temperature of steel defines phase transition between two phases of steel. As the steel is heated above the critical temperature, about 1335°F (724°C), it undergoes a phase change, recrystallizing as austenite. There are two types of critical temperature:

- Lower critical temperature (Ac1). The temperature at which austenite starts to transform from ferrite.

- Upper critical temperature (Ac3). The temperature at which austenite is completely transformed from ferrite.

The Fe-C system has a eutectoid point at approximately 0.8wt% C, 723°C. The phase above the eutectoid temperature for plain carbon steels is known as austenite or gamma.