In comparison to internal flow, entrance flows and external flows feature highly viscous effects confined to rapidly growing “boundary layers” in the entrance region or thin shear layers along the solid surface. Accordingly, there will always exist a region of the flow outside the boundary layer. In this region, velocity, temperature, and/or concentration do not change in, and their gradients may be neglected.

This effect causes the boundary layer to be expanding, and the boundary-layer thickness relates to the square root of the fluid’s kinematic viscosity.

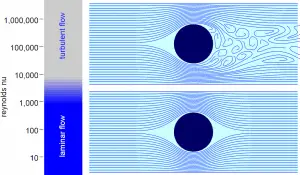

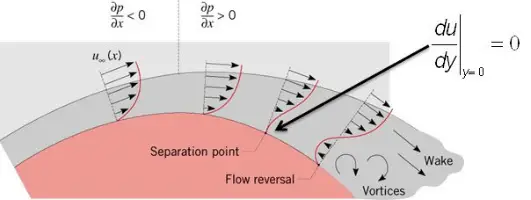

This is demonstrated in the following picture. Far from the body, the flow is nearly inviscid. It can be defined as the fluid flow around a body that is completely submerged in it.

Fluid Flow over a Flat Plate

In general, when a fluid flows over a stationary surface, e.g.,, the flat plate, the bed of a river, or the pipe wall, the fluid touching the surface is brought to rest by the shear stress at the wall. The boundary layer is the region in which flow adjusts from zero velocity at the wall to a maximum in the mainstream of the flow. The concept of boundary layers is important in all viscous fluid dynamics and the theory of heat transfer.

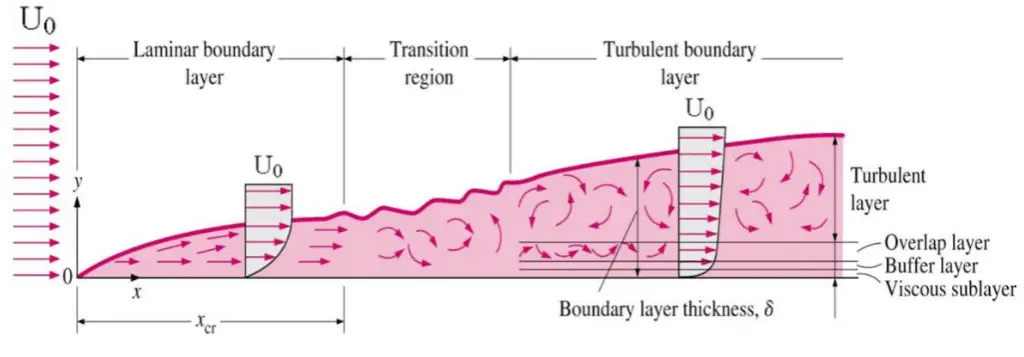

Basic characteristics of all laminar and turbulent boundary layers are shown in the developing flow over a flat plate. The stages of the formation of the boundary layer are shown in the figure below:

Boundary layers may be either laminar or turbulent, depending on the value of the Reynolds number.

See also: Boundary Layer

Nusselt Number

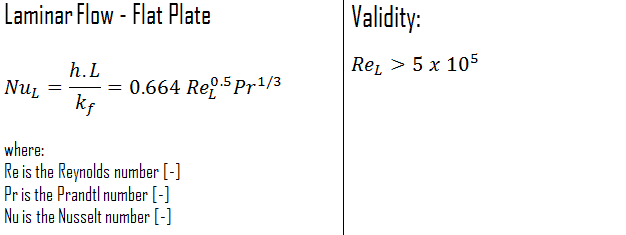

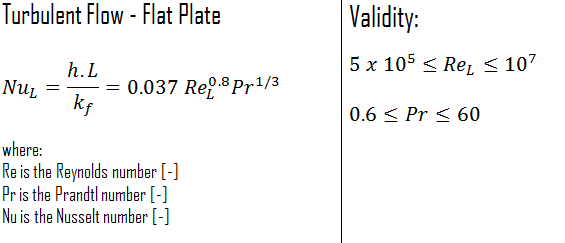

The average Nusselt number over the entire plate is determined by:

This relation gives the average heat transfer coefficient for the entire plate when the flow is laminar over the entire plate.

This relation gives the average heat transfer coefficient for the entire plate only when the flow is turbulent over the entire plate or when the laminar flow region of the plate is too small relative to the turbulent flow region.

Tube in crossflow

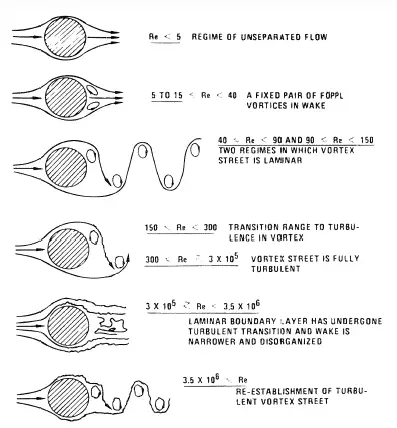

The crossflow of tubes or cylinders shows many flow regimes that are dependent on the Reynolds number.

- ReD < 5. At Reynolds numbers below 1 no separation occurs.

- 5 ≤ ReD ≤ 45. In this Reynolds number range, the flow separates from the rear side of the tube, and symmetric pair of vortices are formed in the near wake.

- 40 ≤ ReD ≤ 150. In this Reynolds number range, the wake becomes unstable, and vortex shedding is initiated.

- 150 < ReD < 300. In this Reynolds number range, the flow is transitional and gradually becomes turbulent as the Reynolds number increases.

- 300 < ReD < 1.5·105. This region is called subcritical. The laminar boundary layer separates at about 80 degrees downstream of the front stagnation point, and the vortex shedding is strong and periodic.

- 2·105 < ReD < 3.5·106. Three-dimensional effects disrupt the regular shedding process, and the spectrum of shedding frequencies is broadened. With a further increase of ReD, the flow enters the critical regime.

- ReD > 3.5·106. This regime is called supercritical. In this regime, a regular vortex shedding is re-established with a turbulent boundary layer on the tube surface.